The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow is a British folk horror point-and-click adventure game from Cloak and Dagger, published by Wadjet Eye. The latter is a long-time favourite studio of mine, as previous game reviews on this blog will attest.1

The protagonist of Hob’s Barrow is one Thomasina Bateman, an antiquarian primarily interested in digging up barrows (burial mounds) across England. The game is set in Bewley, a remote Midlands village surrounded by desolate moors, sometime during the Victorian Era. Thomasina2 receives a letter from a gentleman named Leonard Shoulder, who invites her to the village to excavate a local barrow. Upon her arrival, Thomasina meets a cast of eccentric and unwelcoming townsfolk, none of whom seem willing or able to tell her much about the supposedly famous landmark or her elusive contact Mr Shoulder. Being a stubborn sort, she presses on anyway, determined to find the barrow and uncover its secrets.

The eastern edge of Bewley.

# Gameplay

The game takes place over a few days, during which Thomasina must explore the village and complete errands for its inhabitants so she can locate and ultimately excavate the titular Hob’s Barrow. The interface is standard for modern adventure games – left-click to interact, right-click to examine, and mouse over the top of the screen to see the inventory. Modern conveniences such as a fast-travel map and to-do list/quest log are welcome inclusions, and there’s also a neat time-saving mechanic that allows you to instantly exit a room by double-clicking.

Thomasina is an upper-crust lady of means, but for gameplay reasons runs out of cash early on, and so must embroil herself in some classic adventure game puzzle solving to get anything she wants – the plot advances through such staples as elaborate NPC distraction puzzles and long chains of fetch quests.

There’s also a bit of digging, as one might expect from the title.

Despite my love of the genre, I must confess a distaste for these sorts of puzzles, at least outside of comedic works like Sam & Max or Flight of the Amazon Queen. I’ve previously praised other Wadjet Eye games (Unavowed, Technobabylon, Blackwell Epiphany) for puzzles that felt like integrated parts of the story and game world. On this count Hob’s Barrow is not a complete success. The better puzzles are used to explore the game’s cast and deepen Thomasina’s relationships with them, and contain some touching character moments. Other puzzles feel a lot like padding. One chain, involving a broken fiddle bow, exists only to facilitate a set piece that, while appropriately unsettling, feels poorly integrated into the overall story. Another chain, involving a pail of milk, is yak-shaving exemplified and contains an NPC-distractions puzzle that felt a little too comical for the game’s general tone. But there are enough strong moments and interesting plot twists in this segment of the game for me to overlook even the weaker puzzles.

The final section of the game, which involves actual barrow excavation, consists of a different sort of traditional adventure game puzzle, but one which gels perfectly with the game’s tone and plot, and actually feel like the sort of thing a proto-archaeologist in this kind of story should be doing. Though I wouldn’t go so far as to say the game would have been better with more focus on this section – there’s an undeniable charm to the village of Bewley and its inhabitants that Hob’s Barrow would be much poorer without.

A garden in the sky.

My first playthrough took about ten hours. I’m compulsive about examining everything and exhausting all dialogue options, so that’s probably close to the upper bound of how long you can spend with this game if you don’t get seriously stuck.

# Presentation

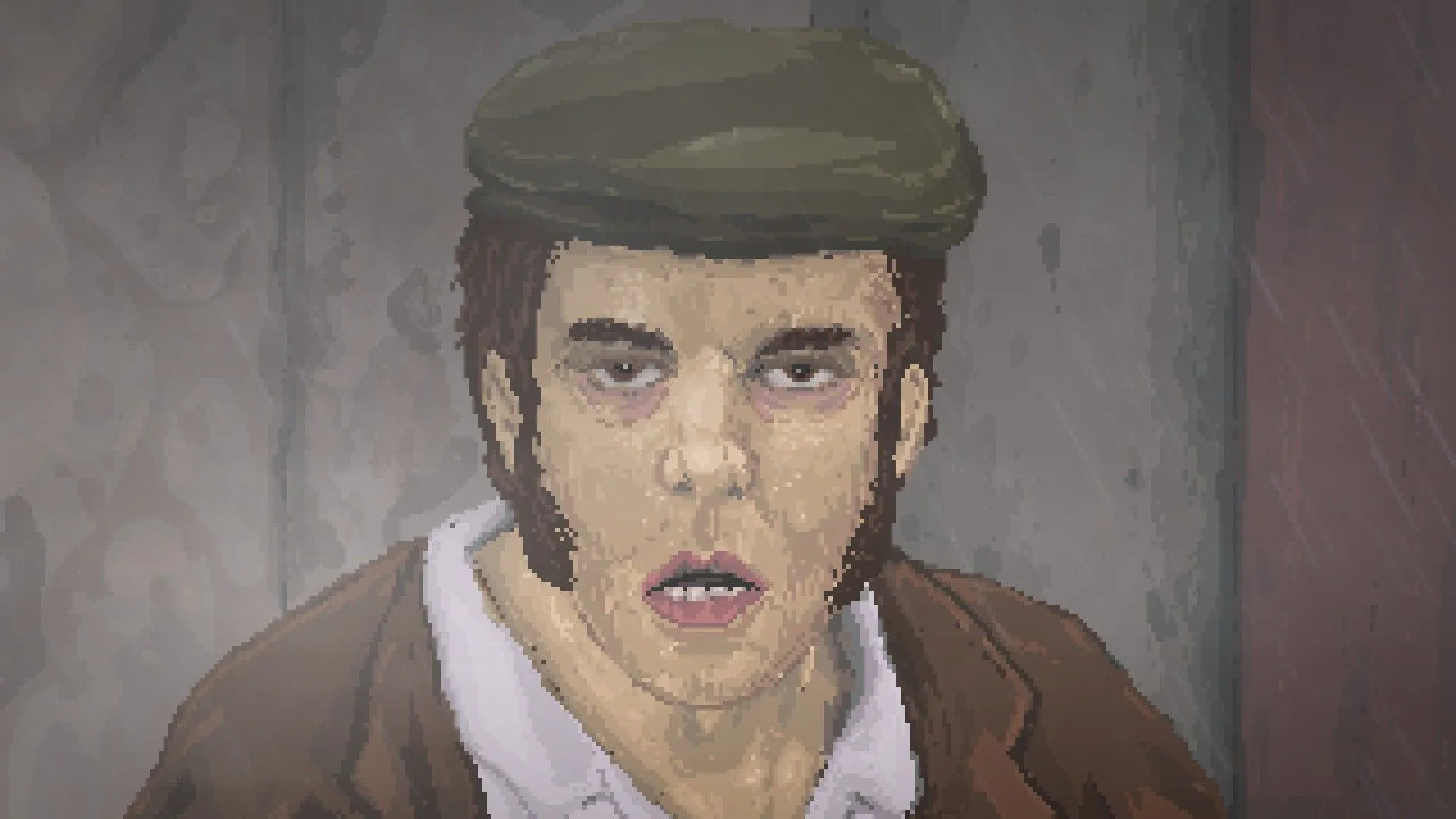

At first blush, the graphics are standard for a Wadjet Eye game – 2D pixel art that mimics VGA adventure games of the early-to-mid 1990s. It’s beautifully done, with many background animations that make every scene feel alive. More modern-looking particle and lighting effects are used to good effect for rain and fog.

Bewley at night.

The game distinguishes itself with detailed close-up animations for dramatic and creepy moments. While none of them are out-and-out jumpscares, they’re very unsettling.

Though a few of them are quite pleasant. Incidentally, this is the least creepy image of this cat in the whole game.

The voice acting is up to Wadjet Eye’s normal excellent standard, and it’s a welcome change of pace to hear British accents in one of these games. “There’s nowt for you ’ere, lass,” will be echoing in my brain for at least a few more weeks.

The music is understated and contributes to the atmosphere. Apart from background music, there are a couple of musical performances in the game, both of which are great, even if one feels a touch modern for Victorian England.

# Story

Vague spoilers follow.

As is common for the horror genre, and especially for works inspired by Lovecraft, Hob’s Barrow does not have a happy ending. Choices made during gameplay lead to variations in character dialogue, but there’s only a single ending – nothing you can do will save Thomasina from the fate she hints at in the game’s sombre narration, framed as a letter to her mother written after the game’s events. It reminds me of another adventure game about a highly characterised adventurer archaeologist excavating a tomb.

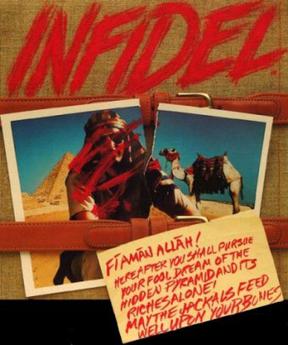

Infocom’s Infidel, released in 1983, was likely the first adventure game to feature a strongly defined player character who meets an unpleasant end after the player “wins”. In that game, you take on the role of an assistant to a famous and successful adventurer-archaeologist in the cast of Indiana Jones. After receiving a call from a wealthy benefactor wanting to sponsor an expedition to an Egyptian pyramid while your boss is out, you decide to take on the job alone, without informing your boss about it. This doesn’t go well, and the game proper begins like this:

You wake slowly, sit up in your bunk, look around the tent, and try to ignore the pounding in your head, the cottony taste in your mouth, and the ache in your stomach. The droning of a plane’s engine breaks the stillness and you realize that things outside are quiet – too quiet. You know that this can mean only one thing: your workmen have deserted you. They complained over the last few weeks, grumbling about the small pay and lack of food, and your inability to locate the pyramid. Ander after what you stupidly did yesterday, trying to make them work on a holy day, their leaving is understandable.

And after some hours of deciphering pseudo-hieroglyphics, solving mechanical puzzles, and classic adventure game treasure hunting, it ends like this:

You lift the cover with great care, and in an instant you see all your dreams come true. The interior of the sarcophagus is lined with gold, inset with jewels, glistening in your torchlight. The riches and their dazzling beauty overwhelm you. You take a deep breath, amazed that all of this is yours. You tremble with excitement, then realize the ground beneath your feet is trembling, too.

As a knife cuts through butter, this realization cuts through your mind, makes your hands shake and cold sweat appear on your forehead. The Burial Chamber is collapsing, the walls closing in. You will never get out of this pyramid alive. You earned this treasure. But it cost you your life.

This was highly controversial and arguably led to Infidel’s commercial underperformance. While adventure game players would have been no strangers to a grisly death, for it to be presented as the game’s winning ending was a highly unwelcome surprise. It raised new questions about storytelling in games. Could “winning the game” be reconciled with experiencing an unhappy ending? And how should one reconcile the tragic arc of a highly characterised protagonist with the player’s agency?

Nearly forty years later, the ending of Hob’s Barrow has been similarly controversial, though a much better game and story. Infidel tells the story of an irredeemable bastard getting his comeuppance, whereas the protagonist of Hob’s Barrow is an immensely likeable character whose undoing results from her love for her father.

While both stories have their endings firmly locked in from the start – Infidel because it starts after your character has already doomed himself to a lonely death in the desert, and Hob’s Barrow through its framing device – there’s a sense that you might have more control over Thomasina’s fate because you can direct her actions from the moment she arrives in Bewley. The developers could have included an option somewhere to make her wait for the next train out of town and leave the burrow unexcavated, though this wouldn’t make for much of a story.

Many games with well-defined protagonists have been made in the last forty years, and the compromise between this and player choice seems to be giving the player choices between different in-character options. I think most modern players can accept this, and that’s very much the case in Hob’s Barrow. When you encounter a drunkard near the start of the game, you choose whether Thomasina slaps or fobs him off verbally, but there’s no option for her to kill him.

Charming.

We can apply the same logic to the overall narrative – Thomasina is driven by compulsions at the core of her personality to excavate the barrow despite the warnings and suspicious behaviour of the townsfolk – to run away would be out of character. I think this is what the writers were going for, and while I’m not opposed to it in principle, a couple of missteps make it less effective than it might have been.

Just before the game’s final segment, a friendly character indicates that he has something important to tell Thomasina that he’s been struggling to remember. The contents of his message are shown to us in a flashback sequence, which reveals a very subtly hinted-at twist. We then return to the present, where another character appears on the scene and shoos away the messenger. It is unclear whether we’re supposed to understand that he told Thomasina the contents of the flashback, or that he was shooed away before he could tell it to her. Neither interpretation is particularly satisfying.

If Thomasina is supposed to be ignorant of the flashback’s events, then it doesn’t fit into the framing device of the letter she’s writing. Besides that, there’s something extremely frustrating about having to direct a character’s actions while knowing that they’re missing an important bit of information you have no way of communicating. I don’t think dramatic irony works in an interactive story.

On the other hand, if Thomasina is supposed to have heard the message, then it’s bizarre that she has no reaction to it and never mentions it again. There’s a difference between having your fate bound up in a tragic personal flaw and just being stupid – imagine a version of Romeo and Juliet where Romeo receives the letter from Friar Laurence but still kills himself.

In the game’s commentary, writer and programmer Shaun Aitcheson mentions that the flashback was added pretty late in the game’s development, after it became clear that testers needed something more to understand the story. I think a better approach would have been to pepper the game with additional foreshadowing and only reveal the twist at the end. Sure, there probably would have been accusations that it came out of nowhere, but this game’s ending was always going to be controversial. Any twist ending, no matter how carefully written, will come off as incongruous to some and obvious to others.

For a tragic story about a flawed protagonist to work in a game, it’s essential that the player comes as close to that character as possible and really understands their perspective, to the extent of being blinded by it. Hob’s Barrow undermines itself by stepping away from that to telegraph its ending.

# Conclusion

Despite my quibbles with some of the game’s puzzles and storytelling choices, I had a great time with it overall and would heartily recommend it to fans of indie adventure games and folk horror. That said, players who prioritise their own agency and ability to choose between multiple endings may want to steer clear.

-

When I was looking into Cloak and Dagger’s previous work, I discovered that they were behind A Date in the Park, a free-to-play adventure game that I rather disliked and left a snippy negative Steam review for. This game is much better! ↩︎

-

An old-fashioned female name often shortened to and now subsumed by variants of Tamsin. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.