The point-and-click adventure is often maligned for poor story-gameplay integration. This hidebound genre, with gameplay that varies little between titles, can make the most exciting stories and settings feel like a chore. At their worst, adventure games are like movies that pause at intervals and make you solve a Rubik’s cube to continue watching. But at their best, adventure games can be both cerebrally and narratively satisfying experiences, perfect for players less interested in tests of their reaction times and more interested in tests of their problem solving abilities.

Wadjet Eye, the foremost creator of new 2D point-and-click adventure games, have gotten pretty good at showing that ludonarrative dissonance is not an inescapable genre feature, with strong adventure game stories that are enhanced by their interactivity. Their newest game, Unavowed, continues this proud tradition while introducing a number of small innovations that strengthen an already strong formula.

# Graphics

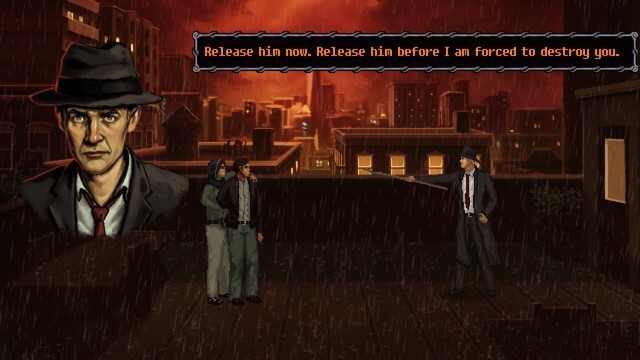

In Unavowed, Wadjet Eye makes the technological leap from a 320x200 to a 640x400 screen resolution. This is still much, much lower res than most modern games, but to a long-time fan of their games, feels like a leap to 4K. This means both crisper pixel art and easier-to-read in-game text, something I wished for in Technobabylon.

The crystal is a magic phone.

The in-game art (barring character portraits) is the work of Wadjet’s in-house artist Ben Chandler, a pixel artist whose work started out appealing and just gets better the more games it appears in.

# User interface

Something that I don’t think has been discussed enough is the game’s UI, and so I will now dedicate a large portion of this review to doing exactly that. Skip this section if you’re not interested in the minutiae of adventure game UIs.1

More than most genres, the point-and-click adventure game has a few standard UIs, with only small variations between games. Since the first graphical adventures from Sierra in the 1980s, this UI has very, very slowly grown away from the text parser of the text adventures that preceded it.

In the original King’s Quest, players typed commands like EXAMINE TREE and GO NORTH (X TREE and N for short), and this continued until the mouse became common and users could instead click on a verb such as look or walk from a menu and apply it to an on-screen object (hence “point-and-click”). These menus started out by including the majority of common text parser actions: examine, push, pull, give, take, talk to, use, open, close, and so on.

So many choices!

At some point, designers figured out that most objects in most games only responded to two of these verbs, and so the menu was condensed to look, talk to and a generic use verb that covered pushing, pulling, opening, closing and all manner of other actions in a context-dependent fashion. Unnecessary mouse movements were also reduced by changing the static menu of verbs at the bottom of the screen (as in Maniac Mansion) to either a series of mouse cursors (used by VGA Sierra games) or a verb coin/pie menu (as in The Curse of Monkey Island – also see The Sims for a non-adventure game example).

This could be pared down further to just look and interact, the latter of which would trigger a use action on an object and a talk action on a person. In 1994, Beneath a Steel Sky perfected the adventure game UI by mapping look to the left mouse button and interact to the right, obviating the need for verb menus or cursor modes.2 Some games, such as Telltale’s Sam & Max series, took this further still by using only the left mouse button as a contextual “look at OR interact” command, which is a little less verisimilitude than I personally like.

Beneath a Steel Sky is available for free on GOG and is well worth your time.

The majority of Wadjet Eye’s games use the Beneath a Steel Sky scheme but with the opposite button mapping, perhaps suggesting characters more inclined to action than examination. Unavowed provides the first innovation to this scheme I’ve seen that makes me think the previous scheme might not have been perfect after all. In previous games, right-clicking an object would bring up a textual description or prompt some descriptive dialogue from the player character, but in Unavowed this is replaced with a brief sentence about the object that appears when you hover your cursor over it.

While I appreciate having separate look and interact actions, the look action is in many ways a vestige of X ITEM from text adventure days, where you had to summon up a detailed textual description of something briefly mentioned in a room description. It stops the action, and to a sufficiently OCD player can reduce gameplay to a sluggish crawl. This is worse in games with multiple player characters, where each item–player combination gets its own description. I never finished Two of a Kind because every time I’d enter a new room I’d exhaust myself reading all the object descriptions from both player characters’ perspectives. In Unavowed, this laborious process is reduced to a few seconds of mousing around, and then you can continue on with the game.

Moreover, Unavowed’s hover-text feels like the act of looking at something in the real world. Rather than making a detailed comment about every single object and person in every room, your character briefly thinks about each thing they glance at in parallel with the action. I hope to see more adventure games use this scheme in future.

This is much more polite than blurting out opinions of random strangers.

# Story & gameplay

Unavowed takes place in the urban fantasy milieu of the sort popularised by The Dresden Files. You’re in a lovingly rendered modern-day New York City, but there are fantastic creatures from a diverse array of mythologies hanging around, carefully hiding from the sight of normal human beings. Thankfully, this game has far fewer (zero) sexually charged descriptions of flayed corpses than its inspiration.

The setting is shared with Wadjet Eye’s completed Blackwell series of games and considerably expands on its lore and mechanics. There’s even a character who does the same Sixth Sense ghost-helping thing Rosa Blackwell spent five games on, though that’s not the central focus this time round.

Uncommonly for this genre, your player character is a lightly characterised individual whose name, gender and history you get to choose. The player character is, roughly speaking, you, which Unavowed plays with in some interesting and surprising ways.

The game starts with an exorcism, in which you must ‘remember’ who you are to choose your character.

The story is divided into a series of self-contained episodes following a larger narrative arc, much like the dramatic television series that have been overtaking the cultural import of films since Netflix switched from mailing DVDs to streaming on the internet. This is a format that works, and it provides a natural way to play the game over a few days or weeks.

At the start of each episode, you choose two members of your party to accompany you. Apart from giving the game some replay value uncommon to the genre, this means each stage’s puzzles had to be designed with several different character combinations in mind, giving the gameplay a flexibility also uncommon to the genre. Rather than feeling like you need to read the designer’s mind to solve the next puzzle, you generally feel that you have an array of sensible choices and actions available to progress.

Puzzles largely make sense in context, generally contribute to world and character building, and never make you build Rube Goldberg machines to accomplish simple tasks. There are some obviously contrived challenges, but these are few and far between. Each episode also contains a meaningful and difficult moral choice, so you’re not just solving puzzles to advance an entirely predetermined story.

A lot of work has gone into making the game world feel alive and dynamic through small touches. The characters in your party will spontaneously engage in conversation as you’re walking through different settings, suggesting unique and carefully thought-out relationships between them. Depending on the character background you choose at the beginning of the game, different characters you run into may recognise you, and different actions are available – for example, the actor background allows you to lie convincingly, and the bartender background gives you a relationship with a recovering alcoholic character.

The game begins in different locations depending on your chosen profession.

# Conclusion

Unavowed is a very good adventure game with a strong, mature narrative, robust puzzle design and rare crossover appeal to people who might not normally enjoy the genre. It’s got likeable characters, meaningful and difficult choices, and excellent pixel art. I also really, really like the UI.

From the social media buzz, it appears to be Wadjet Eye’s most successful game to date. This success is richly deserved. Go play Unavowed.

-

As far as I’m aware, this brief rundown is basically accurate, but I haven’t done exhaustive research into this subject and welcome corrections. ↩︎

-

Contextual pie menus (ala Life is Strange) are the best verb menus, but they feel a bit unnecessary in games that only use two verbs per object and give you “I can’t do that” responses for everything else. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.

Dave Gilbert said on

0 February 2019:

Dave Gilbert said on

0 February 2019: