The Magic Circle is a first-person puzzle game by Question Games. It is also a “genre-obliterating 1st person epic” by Ishmael Gilder’s TMC Games. Like The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Infinite Jest, it’s a work about a fictional work that bears as its own title the title of said fictional work, causing much confusion. To alleviate as much of that as possible, I’m going to be referring to the real game as The Magic Circle and the in-universe game as “The Magic Circle”.

Minor spoilers ahead.

At least this one’s a circle.

# Story

The Magic Circle opens on Gilder rehearsing a narration of the opening cutscene for “The Magic Circle”. It’s pretty standard fantasy stuff, and so the meat of the scene is Gilder getting interrupted by Maze Evelyn, “The Magic Circle”’s lead designer and Gilder’s opposite in design philosophy – where Gilder wants to tell stories and create art with the game (and is really pompous about it), Maze hates story and just wants to focus on gameplay. And that they’ve both been working on finishing this game for many, many years strains their relationship even further than their differences in design philosophy.

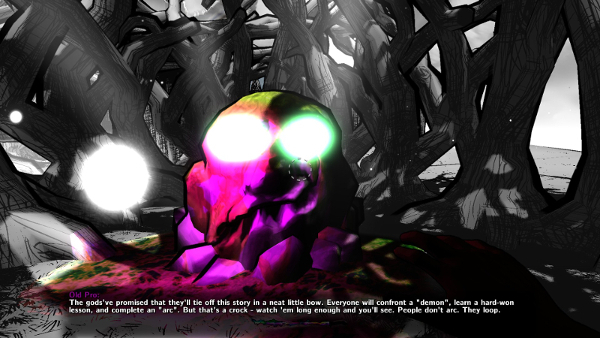

From the moment you start the game, it’s pretty clear that “The Magic Circle” is very much unfinished, possessing all those classic in-dev hallmarks such as placeholder text, 3D models without proper textures and various messages and comments scattered around the levels.

Thankfully, you don’t play this game for very long. In an amusing dig at pacifistic art games, Gilder removes all of the game’s weapons just before you get your first sword, rendering you unable to fight any of the game’s many enemies. After unavoidably dying, you become a ghost and meet a strange entity with flashing multicoloured eyes called the Old Pro.

“People don’t arc. They loop.”

The Old Pro comes from a previous, science-fiction-themed iteration of “The Magic Circle”. He’s gotten really, really tired of the game’s development dragging on as it has for twenty years, and has developed an intense hatred for the developers, whom he calls “Sky Bastards”. He gives you access to the game’s debugging interface for nebulous reasons that become clear later on, and then the real fun begins.

From this point on, you use your new abilities to alter the game to your advantage, changing enemies and bringing back deleted areas, and ultimately fighting and killing the in-game avatar of one of the Sky Bastards and gaining an even greater level of control over the game world.

One of my early game creations, Alternate Path, was based on some similar concepts to The Magic Circle. In Alternate Path, I had the player start the first level in a fairly boring, generic platformer in which you had to jump on enemies’ heads.1 At the end of the first level, however, you’re informed that the rest of the game has been blocked by an evil presence of some kind, and you’re going to have to take a different route to track down this presence and stop them so that the game can continue.

The original plan was to have the rest of the levels be more glitchy and evocative of stuff like Minus World, but at some point that evolved into each of the levels being weird puzzles subverting video game terminology and conventions.2 The Magic Circle takes this idea and related ones a whole lot further than I ever did, and it’s worth playing for that alone. And it also manages to make some interesting points about games, game development and fandom besides.

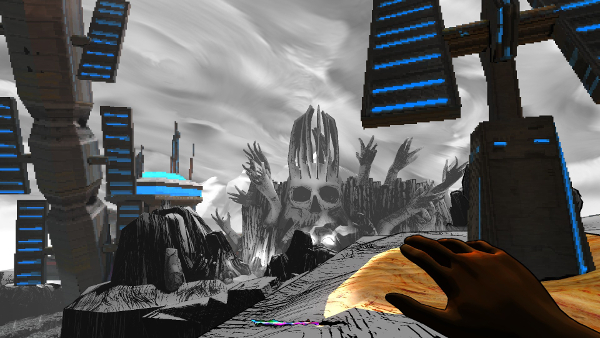

As the game goes on, the Old Pro’s pixelated sci-fi world encroaches more and more on the fantasy setting of newest iteration.

# Gameplay

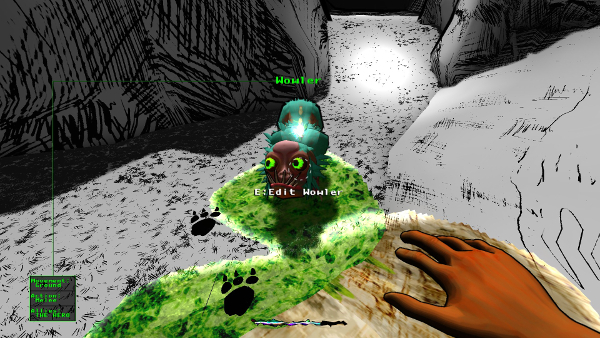

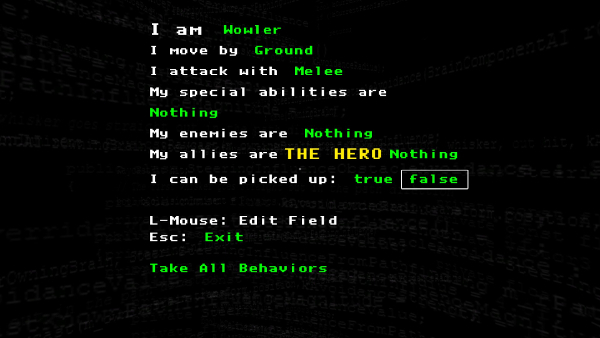

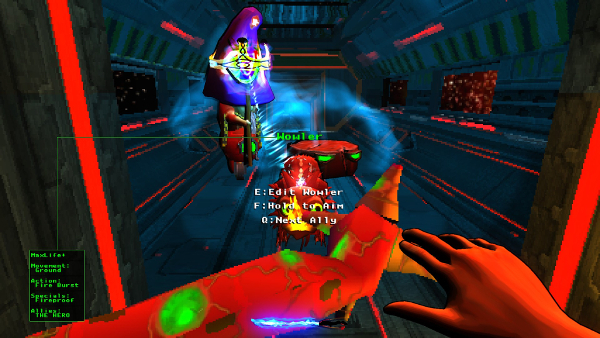

Once the Old Pro gives you access to the debugging features, you’re able to trap and edit creatures in the world. You can’t fight enemies with weapons, so you need to instead trap them and either make them your ally or remove all their abilities so they can’t move or attack you. As the game never gives you a weapon, and you can’t grant any creature’s abilities to yourself, it’s more pragmatic to take the former option and build up a posse of bodyguards.

You can also rename creatures – this enemy Howler became my friend the Wowler.

Anything can be given any movement, attack or special ability, and anything can be made pick-up-able.

This creature editing mechanic forms the core of the gameplay and most of the puzzles. You amass “pets” and trade abilities between the as is beneficial. For example, if you need to get past some fire-elemental enemies, you may grant all your pets the special ability Fireproof, swap out any Flame-related attacks they might have for the more generic like Melee, and then send them in to clear the way.

The puzzles themselves are only occasionally satisfying, however. This sort of gameplay naturally leads to puzzles with multiple solutions and emergent behaviour, but in some ways there’s a little too much possibility. In addition, once you’re hauling around five or six pets with flamethrowers, there’s no need to puzzle out how to defeat a new enemy when you can just send in the horde to wipe it out.

That said, the real failing is in the puzzles themselves rather than the system overpowering you. One gets the feeling that there’s a lot of unexplored potential in the game’s systems and a lot of wicked cool puzzles that just weren’t made. Which could of course be a cute meta design choice to winkingly remind you that “The Magic Circle” is an unfinished game from which a lot of great content was removed for nebulous artistic reasons.

The whole gang’s here, including this previously non-sentient rock.

Once the all-too-brief section of the game dedicated to this mode of playing is over, The Magic Circle turns into something else entirely (the surprise is good enough that I won’t spoil it here) – this section, similarly, is clever but also kind of under-explored.

All of this is over in about five hours, leisurely paced. I’ll take an over-short game with innovative gameplay ideas over an overlong game without them any day, but The Magic Circle is sadly short enough to feel more like a very intriguing experiment than the fully realised classic it might otherwise be.

# Presentation

Being all about about an unfinished game, The Magic Circle’s presentation is often deliberately sloppy. The main game world is largely black and white, and filled with placeholder models and other things that deliberately invoke the appearance of a level editor.

The game’s HUD and various GUIs are mostly hideous, making obscene overuse of a font that looks like Microsoft’s “System”. Again, this is for effect, and does add to that unfinished, level editor aesthetic, but it’s still pretty ugly to look at for extended periods of time.

Ditto the sci-fi portions of the game, which are more colourful than everything else, but also very pixellated. Intentional, yes, effective, yes, but also quite hard on the eyes at times.

Parts of the game take place in a science-fiction-themed, System Shock-era iteration of “The Magic Circle”, which was nearly finished but never released.

To reinforce this aesthetic still further, the game’s music mainly consists of violin pieces bookended by whispered directions from the conductor. This is funny the first few times, but gets a little tiresome.

So The Magic Circle’s presentation is very distinctive and memorable, but may grate against some tastes.

# Conclusion

Anyone who enjoyed The Stanley Parable or The Beginner’s Guide should definitely play this. I’d also recommend it to fans of first-person puzzle games like Portal. And if you’re at all interested in games about games, this is a must-play.

On the other hand, if you’re really upset by pixellated graphics, ugly monospaced fonts and deliberately unfinished and sloppy aesthetics in general, or can’t stand games with sub-five-hour playtimes, this may be one to skip.

-

There were supposed to be floating coins too, but I forgot to include those. ↩︎

-

In lieu of actually playing Alternate Path (the graphics suck, a couple of the puzzles are completely unfair, and the platforming’s a bit too floaty), I suggest reading Tom Russell’s review of the game in in Issue #5 of Russell’s Quarterly. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.