As I’ve mentioned a couple times before on this blog, I live in South Africa, a country known for Nelson Mandela, wildlife, gold mines and methods of cooking and drying meat. At the moment, the innocuously named Films and Publications Amendment Regulations of 2020 bill is making its way through our legislative process. It was slated to close for public comment on the 17th of August, but this deadline was recently extended to the 17th of September. The bill makes provisions for criminalising the vast majority of online content (possibly unintentionally). For example, section 28.4 states the following:

No person may host any website or provide access to the internet as an internet service provider, unless such person is registered with the FPB in terms of section 27A of the Act.

As I am not registered with the South African Film and Publications Board, and neither is my (foreign) hosting provider, this website would be illegal under these regulations. Not to mention the strangeness of requiring ISPs to register with a ratings board, or the odd conflation of ISPs and hosting providers. In another part of the bill, ISPs are required to prove they have mechanisms for stopping the distribution of child pornography, suggesting further confusion about what ISPs actually do and how the internet is structured, especially in the age of ubiquitous HTTPS.

Through very liberal definitions of what constitutes a film or publication, the bill also criminalises social media posts and YouTube videos. Now, the FPB has stated that they are only concerned about commercial content, presumably the films, games, books and the like that they have heretofore managed terrestrially and do not plan on using the act to regulate social media, but that’s not what the act says. What their intentions are regarding non-commercial websites such as this one, who can say?

TWEET CONTENT NOT YET RATED

— David Yates (@davidyat_es) March 7, 2017

One law specialist, Dominic Cull, makes the point that the FPB is intended to regulate the entertainment industry and is overstepping that mandate by attempting to regulate speech, which hopefully makes the whole Act unconstitutional. But, to sympathise with the FPB for a moment, the internet age has made the lines between everyday speech and entertainment media a lot blurrier than they once were. And that’s why – moment of sympathy over – their mandate should be as narrow as possible.

Before the Films and Publications Board, there was the apartheid-era Publications Control Board, which censored and restricted media that the regime considered unsuitable for local audiences, mostly sex scenes and interracial relationships. The fear of on-screen race mixing was so great that television only started up in the country in 1976. Had that regime lasted any longer, they might have tried something similar with the internet.

This overt censorship was done away with after 1994 and the transition to universal suffrage. One amusing consequence was that adults rewatching films they’d seen decades earlier were surprised by the presence of some extra scenes. The Publications Control Board was replaced with the Films and Publications Board (FPB), the fairly narrow purpose of which was to provide age restrictions for, well, films and publications. Mangosuthu Buthelezi, the greatest president South Africa never had, drafted the initial Films and Publications Act of 1996, which took a hard line on freedom of expression, allowing censorship only for things like child pornography.

Unfortunately, amendments since then have backtracked, leading to a few cases of politically motivated censorship on the grounds of obscenity. It’s gotten to the point where we’re now looking at one of the world’s worst internet censorship laws (at least in intention). The recently published regulations above are the latest outcome of a legislative process referred to in damning terms by the Electronic Frontier Foundation in 2015:

Only once in a while does an Internet censorship law or regulation come along that is so audacious in its scope, so misguided in its premises, and so poorly thought out in its execution, that you have to check your calendar to make sure April 1 hasn’t come around again. The Draft Online Regulation Policy recently issued by the Film and Publication Board (FPB) of South Africa is such a regulation. It’s as if the fabled prude Mrs. Grundy had been brought forward from the 18th century, stumbled across hustler.com on her first excursion online, and promptly cobbled together a law to shut the Internet down. Yes, it’s that bad.

That the gist of this act remains essentially as bad as it started out five years ago, following plenty of robust feedback and campaigning by various interest groups, is disheartening. Sadly, this seems to be a fixture of internet-related legislation the world over. We’ve seen similar censorship pushes in the UK and Ireland, and every few years some lawmakers get it in their heads to have yet another go at backdooring encryption.

These legal proposals demonstrate an ignorance of how computers and the internet work and an inability to grapple with scale. Lawmakers and governments are stuck in an analogue way of thinking that is fundamentally alien to the digital landscape. The essential misunderstanding here, well articulated by Cory Doctorow in this 2012 piece, comes right down to Turing machines.

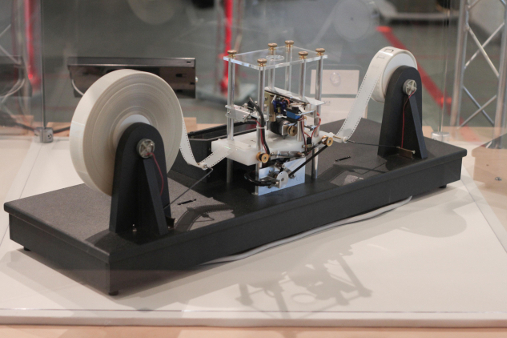

A fully functional computer

In computer science, a Turing machine is a theoretical device that reads and writes symbols on a length of tape. Such machines can be programmed to perform these actions according to particular rules, and in so doing will be able to compute anything. Conceptually, the computer or phone you’re reading this on is a Turing machine with a really long string of tape and an incredibly fast head.

Any limitation of the Turing machine – for example, preventing it from erasing symbols, or only allowing it to move in one direction along the tape – will result in it not being a functional computer anymore. The necessary and sufficient conditions for such a machine to run any program are the same as the necessary and sufficient conditions for such a machine to run every program.

The upshot of this is that it’s impossible to build a computer that can only run “approved” software or view “approved” media. It’s also impossible to build an encryption algorithm that can be broken only by “approved” parties. These facts make unbreakable encryption impossible to ban and unbreakable DRM impossible to create. They make it impossible to impose technically the kinds of abstract restrictions governments and corporations would like to impose. Therefore, as Doctorow points out, the only vaguely effective solution for policing software and content is through spyware.

As it is with computers themselves, so it is also with networks of computers. It is impossible to build censorship technology for blocking obscene content without also enabling the censorship of all other content. As much as we might like to, it is impossible to build an internet that is unable to distribute child pornography. At least, not without creating massive world-wide spyware infrastructure that voids everyone’s rights to privacy. Actually enforcing most of the provisions in the FPB’s bill would require something like that.

In some ways, perhaps, these are not new problems. It is also impossible to create a videotape or roll of film that is incapable of recording illegal material. But it is an order of magnitude more difficult to disseminate such content than it is to disseminate an illegal video or image file. Just as computers streamline and amplify our abilities to store and organise information, to communicate with each other and to solve problems, they also streamline and amplify our ability to do harm. A quote I used in my post about fake news seems appropriate:

When you make something frictionless — which is another way of describing zero transaction costs — it becomes easier to do everything, both good and evil.

Ben Thompson, “The Super-Aggregators and the Russians” on Stratechery.com

This streamlining or frictionlessness is the main thing that trips up legal authorities. The FPB sees its mission as protecting children from violent and sexual content they are not mature enough to process. In the pre-internet era, they could ensure content was rated through physical means, as they dealt with physical media inside the country’s borders. However, in the physical world, the FPB would have no way of controlling or censoring bootlegs or limited distribution media such as flyers or home video, because they would have no control over the distributors. Now that all kinds of media travels along the same series of tubes, they seem to believe their jurisdiction should expand (or at least, that’s what the bill says). Across the world, law enforcement believes it should have access to encrypted WhatsApp messages for the same reason, even though they never would have had access to equivalent communication in the pre-internet era. Arguments for massively expanding jurisdiction are represented as arguments for clawing back territority lost to technological advancements.

Today, the friction of physical media and physical distribution no longer exists, and so the amount of film and media content available to everyone has grown exponentially. Many companies and industries have not yet caught up with this, or are explicitly hostile to doing so, so you have situations where global streaming services have to acquire distribution rights for the same content per country so that they are legally allowed to remove self-imposed region locks (that are trivially bypassable in any case1).

Region locks, localised content rating, and so on, are attempts to add that friction back in, and that seems to be what the FPB would like to do with this bill. In the ideal world the bill presumes to exist, every online streaming service and distributor of films, video games, books, periodicals – heck, every website – would be illegal to access in South Africa until the owner of the platform pays the FPB money to either rate their content or have their existing rating approved. What’s worse, this appears to be an annual fee per item!2

In addition to obligations of money and time, platforms would need to store all kinds of personal information about individuals who view certain categories of content, and comply with “any conditions [the FPB] considers necessary for the better achievement of the objects and purposes of the Act”.

This is all, of course, completely impractical without PRC-level internet surveillance tech or a North Korea-style intranet. If the goal of the bill is just to rate Netflix originals – as a charitable read of the FPB’s public statements would indicate – that’s probably doable, but Netflix isn’t the only game in town, and the fundamental point of the internet is that anyone anywhere can start up a media distribution website with global reach. Moreover, the vast majority of media that falls under the FPB’s actual mandate is already rated by foreign or international bodies, and so this would all need to be done in the name of rerating content. That’s a lot of infrastructure just to turn a PG into a 10V.

No matter the potential for abuse, we cannot sacrifice the democratisation of access to information and to publishing that the internet has brought about. Neither on a moral level, nor on a practical level. The genie is out of the bottle, and hopefully, in time, law-makers will realise the futility of trying to add the friction back in. Cheesy as it is, John Perry Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace is just as true and vital today as it was in 1996 – national borders have no meaning online. The internet is a post-national space that parochial politicians don’t understand3 and should have as little power over as possible. Especially considering that the sheer impracticality of exercising such power means that it will be exercised selectively and probably capriciously.

Which isn’t to say that children shouldn’t be protected from inappropriate content. That the internet makes kids’ access to all kinds of adult materials much easier than it’s been historically is undeniable. But trying to enact this through badly written legislation that demonstrates no understanding of how the internet works or its sheer scale – that viciously tosses the baby out with the bathwater – is not the way to do it.

As with fake news, the bulk of responsibility must lie with individuals. It’s not the government’s job to restrict your kids’ access to the internet. Platforms like YouTube provide child-friendly content modes, and there’s a massive industry of software for blocking inappropriate parts of the web on individual devices and connections. At the level of the individual and the family, censorship is fine and even positive in many cases but – like a lot of bad policy – it just doesn’t scale beyond that.

-

Bypassing region locks being the main feature advertised by most consumer-oriented VPN providers. ↩︎

-

Which makes me think this bill may be less about protecting children and more about raising funds. It’s reminiscent of a proposal from a few years ago to require TV licenses for all devices with screens on the off-chance that you use that screen to watch a YouTube video containing SABC content. ↩︎

-

This article records one government minister’s odd lament that SA doesn’t have locally developed search engines or browsers. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.