# I

Comics rockstar Grant Morrison’s run on DC’s Animal Man (issues 1–26, 1988–1990) is celebrated for its redemption of a ludicrous bit-character from the 60s, its strong political stances and (mostly) its heavy meta elements. It’s of a piece with Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing and Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman – a talented British writer reimagines a D-List character from DC’s half-century back catalogue, showering DC in both money and critical acclaim.

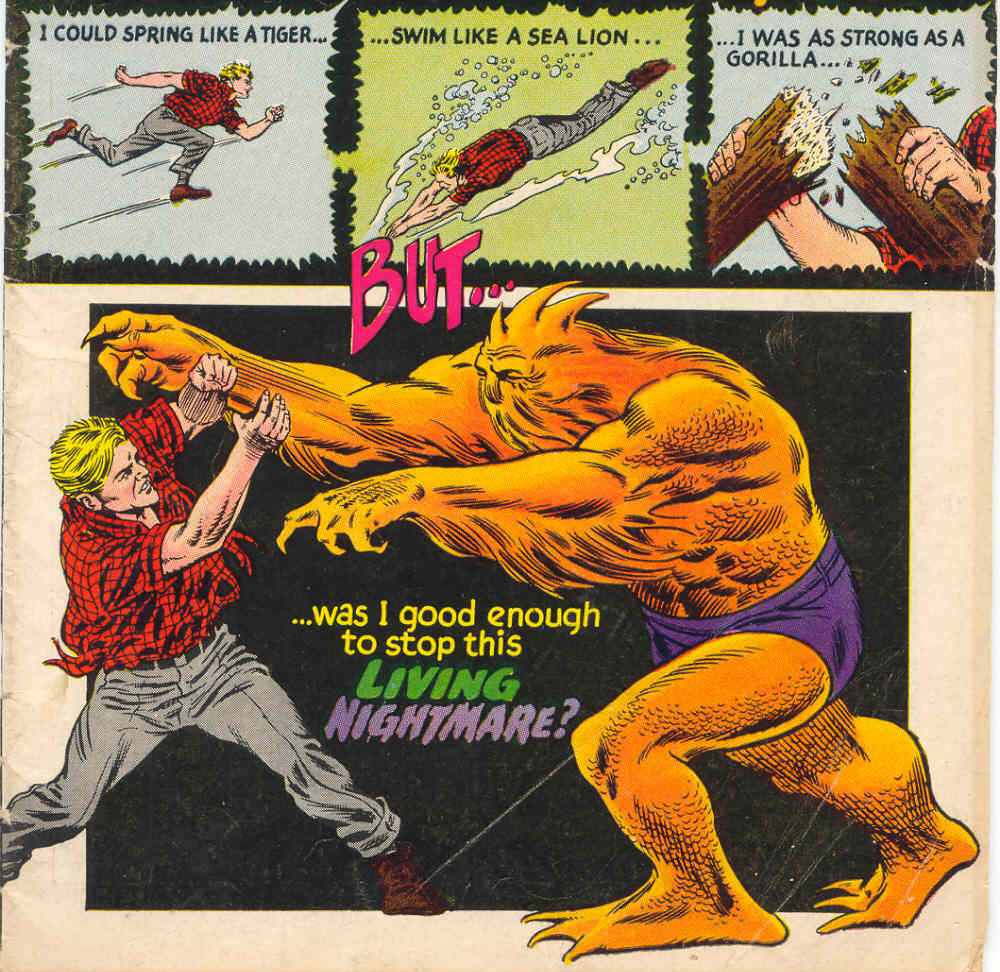

Strange Adventures #180, September 1965

Buddy Baker is Animal Man, Hollywood stuntman and superhero who can take on the abilities of nearby animals without changing appearance in any way. In his original appearances in the 1960s, he mostly took flight from birds, strength from gorillas and occasionally underwater breathing from fish, making him the same as any other superhero but for a different reason. His origin story involved radiation from a crashed alien spaceship and being attacked by both a tiger and a gorilla on a hunting trip in California.

In his first appearance, Buddy is humanised through his nervous, stuttering and ultimately failed attempt to propose to his girlfriend Ellen, but he clearly gets it right eventually, because after his brief appearances in the Strange Adventures, he was seen married to Ellen with two pre-teen children in an 80s issue of Action Comics. This state of affairs apparently dovetailed with Grant Morrison’s desire to write about a superhero with a family and DC’s above-mentioned money-printing machine, and thus 1988’s Animal Man was born.

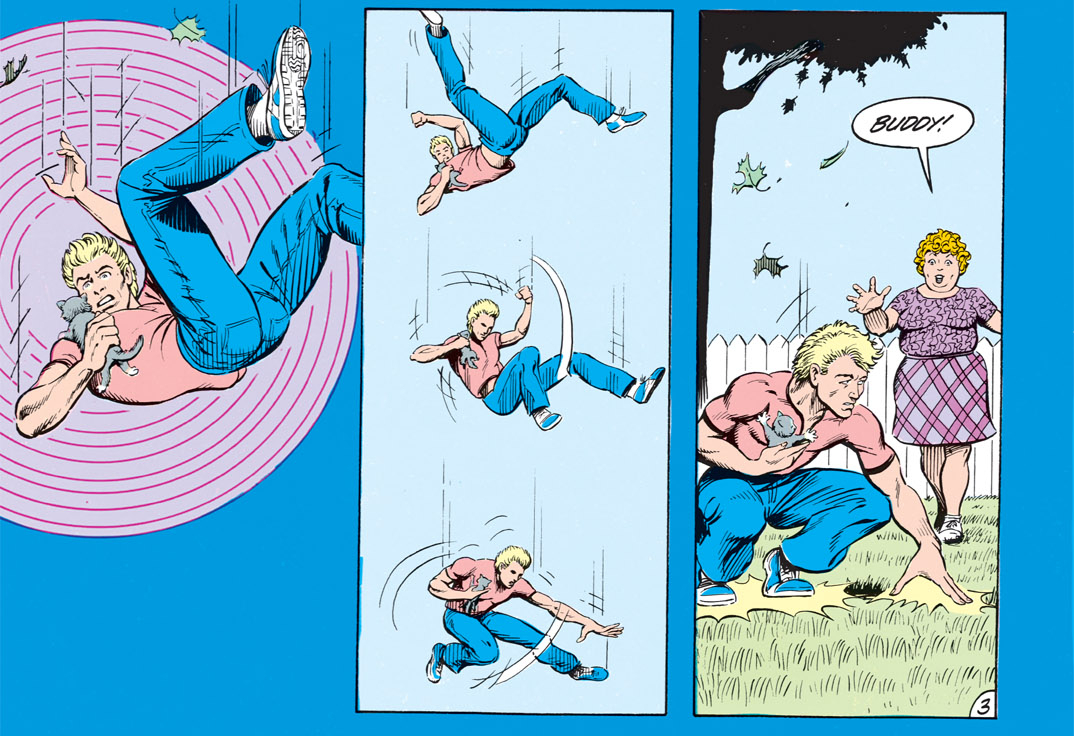

Rather than fighting geographically improbable beasts, Morrison’s Buddy Baker first appears rescuing a cat from a tree and taking on its ability to always land on its feet to avert a nasty fall. This nicely sets the tone for his character and the storylines through the rest of Morrison’s run – this version of Animal Man is highly unlikely to go on any hunting trips, given that he converts to a vegan diet within the first ten issues.

Animal Man #1, September 1988

Buddy starts the comic out as a retired hero, his A-emblazoned costume gathering dust in the back of a closet, which is basically consistent with his previous appearances, but because Animal Man is set after DC’s Crisis on Infinite Earths continuity redo, Buddy gets to have a few details about his life rewritten, so that he’s around the same age in 1988 with a family as he was in 1965 as a bachelor. This will be important later.

Buddy decides to come out of retirement and become a superhero again pretty much on a whim, vaguely inspired by a desire to get famous and bring in money for his family through magazine interviews and talk show appearances. He digs out his old costume, spends some time getting reacquainted with his animal powers, and gets his first assignment from STAR Labs, who ask him to investigate a break-in. This launches a storyline involving B’wana Beast, another forgotten animal-themed DC character1 with the particularly bizarre ability to merge living creatures with each other.

So at the beginning of the series, the idea seems to be to take old ridiculous characters from DC’s back catalogue and redeem them by either taking their powers and backstories more seriously than their original creators did and/or sparking friction between the sensibilities of late-80s Morrison and DC writers from a quarter century earlier.

A particular example of the second aspect comes in issue 13, in which Animal Man teams up with B’wana Beast to find a successor to the latter’s title and powers in the form of a black South African journalist. This is an earnest play at redeeming an outdated idea of an African superhero (and the only reason the character has appeared subsequently) but because of DC’s long continuity, we have story about real-world 80s South Africa set in a world where other African countries include the first B’wana Beast’s adopted home of “Zambesi”, a central African country on the west coast but also near Kilimanjaro. I found the contrast jarring, but that’s comics.

Within about five issues, it becomes clear that Morrison is not content to just redeem ludicrous characters and explore the implications of Animal Man’s powers. Animal Man #5, “The Coyote Gospel” points the series in a bizarre direction that will eventually come to dominate it. This is where things get meta.

# II

I’m not a huge fan of massive continuity. Having a whole bunch of characters and stories in a single shared universe where they can run into each other and influence each others’ stories, and having that happen in a single continuity that’s been going for nearly a century sounds cool in the abstract, but it’s exactly how you end up in situations where you have to write serious stories involving the indeterminately located African mash-up country of Zambesi. It’s also a total stakes killer – how can anything really matter in a world full of wizards and space aliens and time-travellers who can just reverse anything that happens (and probably will, sooner or later)?

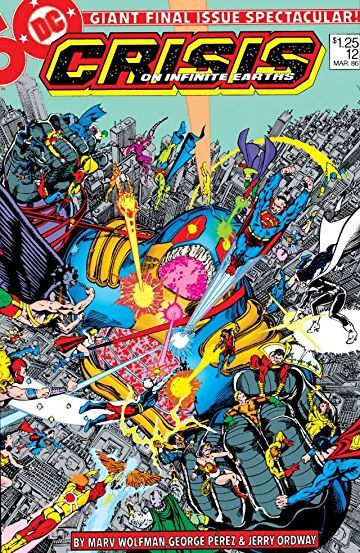

Crisis on Infinite Earths #12, March 1986

The most notable giant alteration of continuity in superhero comics is probably DC’s Crisis on Infinite Earths, a book-keeping exercise in the form of a massive multi-crossover event, in which DC compressed the various alternate dimensions that made up its shared universe into a single coherent whole. Through various timey-wimey shenanigans, characters were merged, histories were rewritten (not least of all Buddy Baker’s, as mentioned above) and a single DC world was shaped from the currently fashionable pieces of a thousand older worlds, all in an effort to make comics less confusing and more approachable for potential new readers.

The later issues of Animal Man (spoiler warning!) are essentially an effort to subvert this clean-up. Buddy Baker starts having visions and dreams of his original, pre-Crisis origin story, which conflicts with the memories of his post-Crisis origin story that are consistent with his current post-Crisis life. At the same time, an alternate version of Buddy starts appearing to members of his family. Various other weird comic stuff happens, eventually culminating in a crazy character who remembers what the world was like Pre-Crisis summoning every character DC airbrushed out of their shiny new continuity to the current Earth, including a mad evil version of Superman with a nuke (presumably from some edgy one-off what-if story). Morrison’s point seems to be that if DC can come up with complicated in-universe justifications for straightening out their continuity, he can come up with complicated in-universe justifications for undoing all that, at least temporarily.

It was nice, wasn’t it? Nice to see all those old characters for one last time, just the way I’d remembered them. I wish they’d stayed. They made the world more interesting.

Psycho Pirate

Rather than even try to couch any of these strange reality-bending events in technobabble about dimensions and timelines, Morrison straight-up uses words like “continuity”, and has his characters realise they’re just characters being written about in story. There’s an inventive sequence where Animal Man escapes into the gutters between the comic frames in order to move through time.

After dealing with the evil Superman and sending all the other discontinued characters away, Animal Man visits a dimension called Limbo, which is where these discontinued characters all live their a vague, story-less existences. Animal Man meets a number of thoroughly unfashionable individuals. And then he meets Grant Morrison. Yeah, it’s like that.

A superhero having a conversation with the author of his comic was probably mind-blowing and original thirty years ago, but now it’s old hat – meta stuff like that is Deadpool’s whole thing, and he’s a lot better known than Animal Man ever was. And The Unbelievable Gwenpool2 ends with a much more upbeat and less wanky-feeling rumination that still hits essentially the same beats. Still, credit where due: Animal Man did it first.

Grant Morrison’s Animal Man is an enjoyable, mostly self-contained ride with strong characters and clever ideas. Time has dulled – but not blunted – its potential to surprise. The meta elements overpowered much of what I liked about the initial issues in a way that reminded me of the things I dislike about continuity-heavy media, but I probably wouldn’t have read or known about it if it wasn’t notable for those elements.

-

With an appellation like “The White God of Kilimanjaro”, you can see why he wasn’t used much beyond the 60s. ↩︎

-

I read individual author runs on superhero comics for one of two reasons: either because they’re particularly notable like this one, or because the author was also responsible for an excellent webcomic. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.