The so-called visual novel is a game format that’s very big in Japan and kind of obscure everywhere else. If you’ve never encountered one, you can think of the genre as computerised puppet theatre with a little bit of audience participation. They tend to be plot-driven affairs with enough gameplay to send a pure ludologist into a frothy rage (i.e. not very much). In the majority of these games1, the player’s input is limited to clicking through dialogue and making CYOA-style choices every few thousand words. Some examples of the genre, called kinetic novels, dispense even with the choices.

So visual novels are a kind of Weird Japanese Thing and a kind of video game without a lot of interactivity. This understandably makes the genre a bit of a ghetto. But what makes it even more of a ghetto is that the Venn Diagram describing the intersection between dating simulator and visual novel could almost be a single circle. The genre, by and large, consists of romcom-type stories about large numbers of girls inexplicably throwing themselves at the generic protagonist. Bit of waste, really.

Thankfully, there are a growing number of exceptions – zoom in a bit, and you’ll see the Venn Diagram is actually two circles. The House in Fata Morgana is one such case – the story is still a romance, at least in part, and you do begin the game as an AFGNCAAP, but as should be evident from the detailed, classical artwork and theatrical soundtrack, this game’s aiming at a higher target. The cover art looks a bit suspect, though (it makes sense once you finish the game).

At the beginning of the game, you awaken in a strange, old and largely deserted manor house. The maid (obsession with old-fashioned European maids is another Weird Japanese Thing) informs you that you’re the master of the house, but have lost your memories. The house has had many masters over the years, and so you will need explore its past to find out exactly which one you are and recover your memories.

The maid first leads you into the manor’s rose garden to tell you about a family who occupied the house in the year 1603. The story that unfolds is about two siblings belonging to a noble family, an older brother and a younger sister. It gets off to a very slow and saccharine start, but events gradually turn for the worst after the family is visited by a mysterious white-haired girl. It ultimately ends in sickening tragedy.

The maid then leads you into the cellar, where you learn about the house’s occupants in the year 1707 – a hideous, murderous beast squatting in a ruined house in the middle of nowhere, and the unfortunate people who stumble upon his dwelling – including a young girl with white hair. Though it hints at the beast’s better nature, and teases redemption, this story ends in violence and tragedy.

You then visit the games room, from whence you observe the house’s occupants in the year 1869 – a wealthy businessman living with an army of servants and a white-haired young wife he mistreats and neglects while single-mindedly advancing his nascent business empire. Great – you guessed it – tragedy arises from miscommunication and the characters’ personal flaws.

The final tale is found at the top of the manor’s tower. It takes place long before the others, in the year 1099, and details the meeting of a young man living under a curse and a young, white-haired woman accused of witchcraft, who end up living together in the house for some time before the by-now-inevitable tragedy overtakes them.

And then the game’s real story begins.

The word “novel” in “visual novel” is not merely aspirational – Fata Morgana is a long story, with a 30-hour playthrough. The four tales described above take up about the first eight hours and work as an extended prelude to the main story. That each one works as a stand-alone story and as an element of a greater whole is a testament to the strength of the game’s plotting.

From the end of the extended prelude on, the story is a rollercoaster of revelations – at every turn, another character’s hidden depths are revealed, casting everything that’s happened before in a new light. Just as you think you’ve found out every secret and figured out everyone’s motivations, the game reminds you of something you missed and reveals that in the most emotionally devastating way possible.

The story deals with deep and mature themes with a nuance not often seen in games. Major characters are uniformly this-could-be-a-real-person complicated, and even the most initially monstrous come to be understandable, and often sympathetic.

The game’s English prose is solid enough to be largely invisible. It’s not sublime or transcendently poetic, but it’s readable and frictionless – words are chosen carefully to evoke a period flavour without alienating readers, and there are few glaring textual missteps. The game reads almost as though it might have been written in English originally, which is not always the case for English translations of indie Japanese games.2

What gameplay there is – opportunities to choose the protagonist’s next action from a menu – is very spaced out and mostly clustered at the end of the game. Most Western story-driven games constantly feel the need to remind you they’re interactive, but Fata Morgana is happy to have you click through dialogue for hours until you forget you’re playing a game, and then suddenly pop a choice up on the screen – in a bizarre design decision, a few of these choices are even time-sensitive.

The lengthy gaps between player interaction allow the game to tell a longer, more complex and more detailed story than if it had to cater for player choice every few screens. As much of the game’s story is backstory, a greater amount of interactivity spread consistently throughout wouldn’t really make sense.

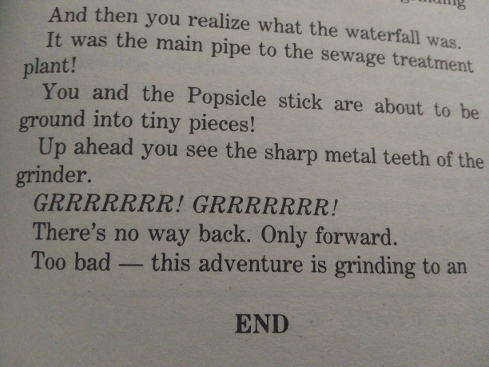

Fata Morgana has eight endings, but as with many interactive stories, only one of them is the “true ending” – reaching this is analogous to winning the game. As a result, if you reach it first, there’s little point in searching out the other endings, as most of them are the VN equivalent of:

RL Stine’s Give Yourself Goosebumps #6: Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter

In a previous review, I asked some questions about what the prevalence of “true endings” like this means for interactive stories. If you’re given choices along the way and different options of how to end the story but one option is clearly the best/intended one, does that mean the whole concept is flawed?

Well, it depends. Some stories work well with true endings – some can even have clear true endings while also having interesting and worthwhile alternative endings – and some stories work best when every ending is ambiguous and bittersweet in a slightly different way. In an interactive medium, it’s preferable if even your “false” endings are interesting and used to explore different aspects of the story rather than just being punishments, but that’s not always feasible or fitting.

All that said, I don’t feel that Fata Morgana would be significantly worse off without its occasional interactive choices and extra endings. The game’s most effective use of its medium comes at a point where it messes with the interface conventions to foreshadow a later development in a way that’s extremely creepy and wouldn’t be possible in any other medium. More meta-interactive than interactive, but it counts.

Game-qualities and interactivity aside, Fata Morgana’s main draw is the engaging story and its beautiful multimedia presentation. The artstyle used for the character portraits is clearly rooted in anime but goes far beyond the norm in detail, colour and shading. Backgrounds are beautiful and impressionistic, if occasionally a little too indistinct.

The soundtrack deserves special mention. Each part of the story is accompanied by a large collection of classical songs fitting the period and atmosphere, most with spoken lyrics in Portuguese, Latin and French3, intended to give the game the feeling of a stage play. It works well.

The House in Fata Morgana is an epic, beautifully presented story. I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys a good story. But if you’re allergic to large volumes of text, slightly animesque art or games that delve only occasionally into interactivity, it might be one to skip.

We should really have a word other than “game” for games like this, but alas, every suggestion sucks. “Storygame” is an ugly word, “interactive experience” is a bit of a mouthful, and “ludonarrative” is even more pretentious than “interactive experience”. So, with apologies to any hardcore ludologists, I’m going to call this thing a game throughout the review. ↩︎

With as much text as this game has, a bad translation would be tantamount to a game-breaking bug. ↩︎

I don’t understand those languages, so I can’t speak to the soundtrack’s lyrical quality. But then I also don’t care much about lyrical meaning. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.