I have a special fondness for space simulators. Two of the first games I ever bought online were Flatspace and Weird Worlds: Return to Infinite Space1, two very different interpretations of the idea that started with Elite in 1984. In all of these games, you pilot a spaceship and fly around the galaxy/universe doing whatever you want: exploring, fighting other ships, trading resources, and so on.

Unlike many other genres of games, the actual gameplay implementation of a space simulator is extremely variable. In Flatspace, you physically fly your ship around space, chasing asteroids with your tractor beams, firing lasers and missiles at enemies and initiating docking procedures with space stations; in Weird Worlds, things are more abstract, and you mostly navigate through menus, interacting on the level of solar systems rather than individual ships, and playing very short games exploring randomly generated galaxies rather than piloting one ship in one game world for hours on end. Another, freeware example of the genre is Yahtzee Croshaw’s Adventures in the Galaxy of Fantabulous Wonderment, which combined space simulator resource management and turn-based ship combat with a straight-forward, linear point-and-click adventure game narrative, puzzles included.

Out There Ω is yet another take on the genre, most similar to Weird Worlds in that (a) doing things in the game is very much an abstracted process dealing with menus and making numbers change and (b) some effort has been made to construct a narrative around the experience. But that’s about where the similarities end.

Whereas Weird Worlds presents the player with an eccentric Hitch Hiker’s-flavoured universe and the task of embarking on a well-funded but time-limited voyage of discovery, meeting, trading with and fighting aliens they meet on the way, Out There casts the player in the role of a hopelessly lost human astronaut with the ever-depleting resources of fuel, oxygen and ship hull integrity, all of which must somehow kept above zero for as long as it takes the astronaut to find their way home. The only aliens the player meets are completely non-humanoid and speak in an incomprehensible babble, and ship-to-ship dogfights are never an option, as the astronaut’s ship is equipped with no weapons.

Both Out There and Weird Worlds have some concept of spaceship storage space – a common feature across space sims. In Weird Worlds you have a certain amount of space for cargo (artefacts and such), and a set number of slots for equipment (thrusters, weapons, informational modules and that sort of thing) with which to enhance your ship (or fleet)’s capabilities. Often you have to make choices about what equipment and cargo to keep and what to throw away, but usually the considerations made are purely monetary – you throw away the stuff that’s worth less money, you replace your various ship parts with more expensive variants, and generally you optimise for asset value at end-game.

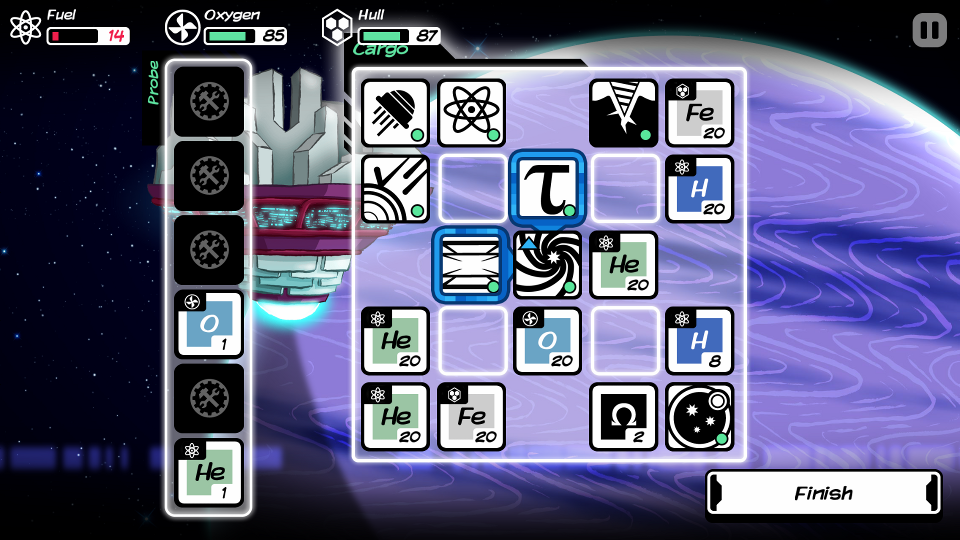

Out There’s storage system is more simplistic: you have a set number of slots, and each slot can contain either equipment or cargo. Equipment is stuff you need to move the ship around (thrusters and hyperdrives), tools for harvesting resources and devices that provide useful informational enhancements to the various menus. Cargo is mostly made up of elements gathered from planets – the important ones are hydrogen and helium (for refilling your ship’s fuel), oxygen (for refilling your ship’s oxygen (duh)) and iron (for repairing your ship’s hull). Other elements can help you build new equipment, but storage preference must be given to these top four (with the possible exception of oxygen, which depletes very slowly and is automatically refilled on landing on a habitable planet).

So unlike in Weird Worlds, if you run out of slots, you have to start deciding between throwing out precious resources and disabling equipment. These decisions are much more grim and uneasy – a wrong choice is much more costly and difficult to avoid. Rather than worrying about the monetary value of your cargo hold, you have to consider whether building this new piece of equipment is really worth throwing out that stock of resources which you may need in order to survive.

Space is the game’s fourth scarce and precious resource: in a brilliant piece of design, no equipment can be destroyed and replaced with a more effective version – rather, enhancements to equipment all require the construction of a separate piece of equipment which must be placed adjacent to what it’s enhancing to provide any benefit. This necessitates careful item placement and mostly retards a typical RPG-type power-creep progression, as the more equipment you build, the less space you have for stockpiling essential resources. Ultimately, a souped-up ship without fuel is as worthless as any other ship without fuel.

The arrows show equipment upgrades.

It’s very easy to come short in Out There if you start throwing out resources, as each of the essential three require elements from different types of planets to replenish. Hydrogen and Helium come from probing gas giants (and suns, if you can build the requisite probe upgrade), Iron can only be mined from rocky worlds, and Oxygen can only be replenished on garden worlds. Naturally, not all solar systems have one of each, and without specialised upgrades, there’s no way to know what’s in store for you at a given solar system until you get there. Hit an unlucky run of systems without gas giants, and you’ll probably run out of fuel and lose the game.

All that said, it is possible to figure out loopholes in the system. In order to do that, you have to start thinking like what the player character is – a desperate scavenger.

One of the most interesting mechanics in Out There is the ability to salvage elements from ship parts. Things like your thrusters and hyperdrive can be cannibalised for their component parts in times of great scarcity. The times I most felt like the lost, desperate astronaut protagonist were the times when I would destroy my hyperdrive to just get enough iron to quickly repair my broken probe so that I could probe for precious Hydrogen, so I could get enough fuel to fly to the next star-system. Most of the time, these desperate attempts left me in worst strait than before, but on a few occasions they pulled me from the brink of being stranded in space and got me safely to the next system.

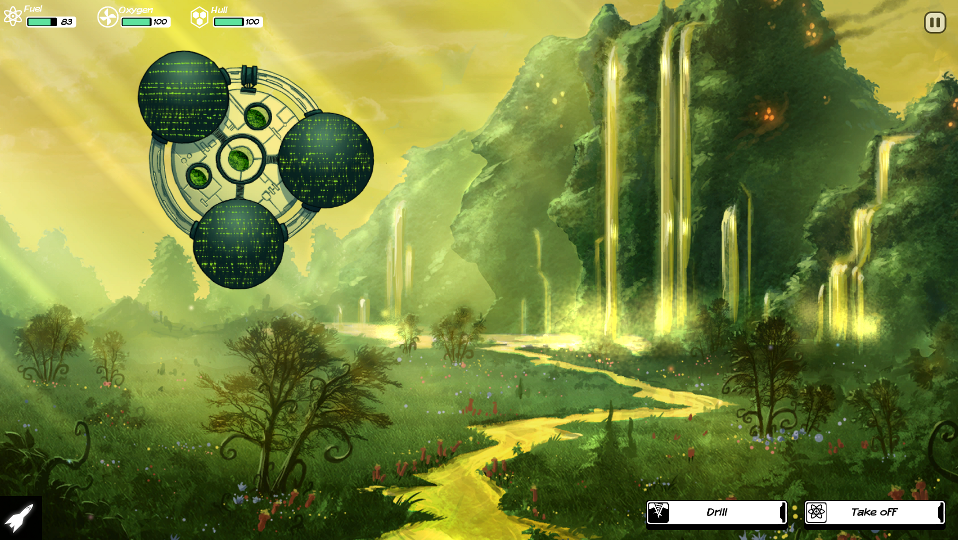

A beautiful garden planet.

When mining or probing for resources, you’re given a slider from one to ten which determines how much fuel you’re going to use dig or probe and therefore how deep you’re going to go. The deeper you go, the more resources your efforts will yield, but the greater chance your have of your equipment being broken or destroyed. So the smart choice initially seems to be to leave the slider at about 5 – you don’t want to use up too much fuel or break anything, but you also don’t want to waste fuel on digging up too small an amount of elements.

However, a problem surfaces from the unpredictability of mining and probing. You can mine or probe a planet multiple times, but you’re going to unearth fewer elements each time, until eventually you waste fuel on digging up nothing. This compounds into a losing situation very fast – if you spend five units of fuel probing for one unit of Hydrogen, you’re only getting another two units of fuel from that, and making a net loss of three units.

There is, however, a trick to beating this system. I just had to get desperate enough to find it. But once I’d found it, my Out There experience immediately became easier. No longer would I die a few systems into each playthrough – now I could actually focus on the grander elements of the game than mere survival: learn the alien languages and pursue the various missions.

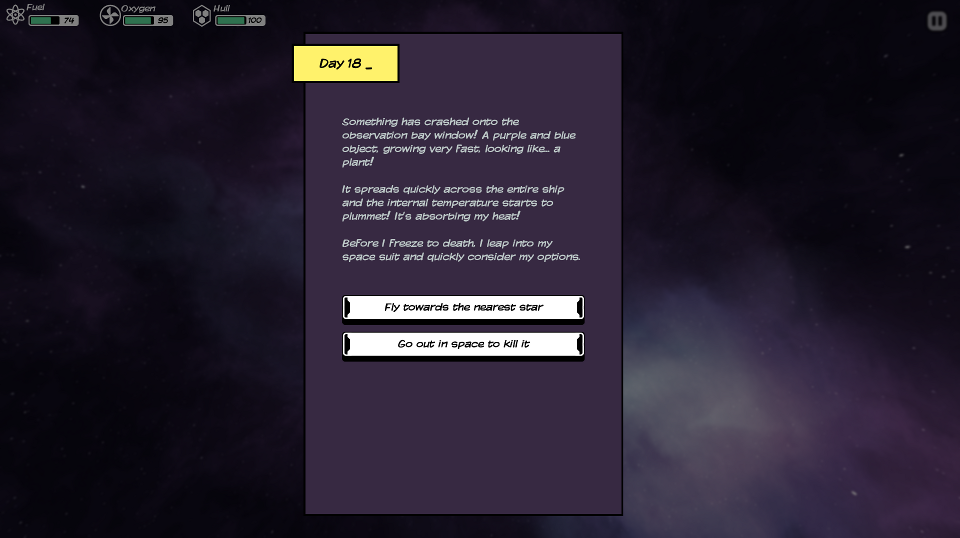

Aside from the resource management, Out There has a number of randomly generated story segments that get shown during hops from star system to star system. These segments usually detail a scenario in which the player character discovers or encounters some derelict ship or bizarre alien lifeform, and the player must make a choice about what to do at some critical juncture and reap either the benefits or damaging consequences thereof, usually related to losses and gains of resources and technologies. But sometimes these story elements just have the player character musing on his travels.

The game also has some neat mechanics regarding aliens. You meet aliens on most of the worlds with breathable atmospheres, and can attempt to talk to them. At first, they speak to you in a random mish-mash of letters, but attempting different actions and saying different things back to them, you slowly piece together enough of the galaxy’s single alien language2 to make these meetings very beneficial.

And so I cruised through the galaxy, mining out planets, building every better equipment and learning alien languages. And then I came on something that made things difficult again. That forced me to make a choice. Spoilers in a hidden box the image.

An example of Out There’s random interstitial story segments.

Click to reveal spoilers

In one of Out There’s rarer random events, you happen upon a spaceship that turns out to be filled with humans in cryogenic stasis. On a story level, this is something you’ve been searching for ever since the beginning of the game, and hinted to be the last members of the race. But on a gameplay level, this is a new and more spacious ship which you need to take if you want to fit more equipment onboard without sacrificing too many resources, and the human bodies take up space. So now the resource choice was between equipment, resources, and cryogenically frozen bodies.

And out the airlock went the last frozen members of the human race.

I played on past this genocide much as before, using the precious space aboard my new ship for equipment and resources, eventually reaching one of the game’s endings. In this ending, the player character discovers that the human race is nowhere to be found in their galaxy, and so he must search the rest of the universe for his people. And this after I had massacred what was strongly hinted at being the last traces of the human race. No acknowledgement beyond a single achievement was made of my heinous act, and so this sad but resolute ending rang hollow.

Not even an icon.

The great power of interactive storytelling, the ability it has that no other form does, is the ability to make the audience feel directly responsible for something, bad or good. A game can make you feel guilt. It can demonstrate a situation, and let you deal with it in different ways, and experience the consequences of your actions. Certainly, it can’t really capture the intricacies and nuance of reality, but it can at least get the broad strokes. And Out There, on this front, really missed an opportunity to do that.

Now that I have it in writing, this looks like a bit of a nitpick, and possibly just a case of me wanting a game to be something it’s not, but then again, Out There works too hard at atmosphere and story for a blunder like that not to be noticeable. That the intended melancholy and resolute hopefulness of the ending can be so thoroughly undermined by player action is a grave error, and really soured my experience towards the end.

There are other paths, and other endings, in addition to those I just spoiled, but the game kind of loses steam once you come to the insight about resource gathering I mentioned above. In a way, the game is most enticing when you haven’t figured any of it out yet and keep restarting just to run out of fuel a few systems in. After that, it’s worth playing till you find out what most of the upgrades do and reach an ending, but much of the magic is lost on subsequent plays. Some more midgame twists to the play dynamic and, of course, a stronger guarantee in the strength of the story would have served well to alleviate this.

You can buy Out There on Steam, or for your Android/iPhone, if that’s your thing. If you’re into space-sims and games with atmosphere and light resource management, it should be just up your alley, and provides at least a few hours of enjoyment. I just wish I could give a stronger recommendation.

-

It came on an ISO file, which I burnt to a physical CD. This was obviously long before everyone was buying all their games on Steam. ↩︎

-

From an immersion point of view, yeah, it kinda bothered me that all the aliens spoke the same language and that all words and writing in the game were said to literally be random jumbles of Roman letters, but it’s something I can forgive as a concession to gameplay. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.