One of the first indie games I ever bought was a little British adventure game called Time Gentlemen, Please!, the commercial sequel to the freeware adventure game Ben There, Dan That! That was about a decade ago. This year, Lair of the Clockwork God has been released as the third game in the series (and the only one with an unpunctuated name).

The first two entries in the series played as fairly traditional point-and-click adventure games, deriving much of their humour from lampooning the conventions of that genre. This one stretches its range, both in gameplay and humour. The premise is this: after spending the previous two games as Ben’s Max-like sidekick, Dan has decided to abandon the adventure game genre for the more hip and relevant indie platformer scene. He has learnt to run and jump and his character design has been changed to a squat, pixelated form with a nose that’s a different colour from the rest of his face. The beginning of Clockwork God finds him eagerly anticipating a new, more impressionistic and allegorical adventure, ala Braid or LIMBO. Ben, on the other hand, stubbornly sticks to the point-and-click format of the duo’s previous adventures, refusing to jump or even walk faster.

Adventurers don’t jump.

Thus, from the start, you find yourself switching between two different games to get past different obstacles. Dan will rush ahead to scout out the map until he runs into an insurmountable obstacle, such as a wall that’s too high to jump over or a cloud of deadly gas. At this point, Ben will amble along behind him, examining scenery and adding loose objects to his inventory as he goes, and solve a puzzle to clear the way, or combine some inventory items to give Dan a new ability. Alternatively, Ben will amble along until he comes to an obstacle, such as a pit or a ledge that can’t be calmly walked over, and then Dan will have to find a way to transport Ben across.

This bifurcated gameplay helps to smooth over the frustration inherent in both composite genres. If you get annoyed at a particularly tricky jump while playing as Dan, you can switch to Ben for a bit and combine some inventory items. And if you get frustrated with an obtuse puzzle as Ben, you can switch to Dan and jump around collecting things. That said, the characters’ interdependence means there will still be points where they bottleneck each other.

Through 21 chapters of varying length, the game comes up with many twists and wrinkles on its basic formula. A few chapters see the two characters physically separated, some are pure puzzle, and others are pure platforming. In a few places, the game even dips into completely new genres. And all this is accompanied by a constant stream of sharp, if occasionally crude, humour.

The main weakness of the dual-genre approach is in the controls. Dan’s platforming is naturally keyboard-heavy, with the mouse used only to move the camera around when you want to see if his next jump’s going to land him on a platform that’s just off-screen or plunge him to his doom. Ben’s adventuring makes much heavier use of the mouse, but its controls appear to have been retrofitted from Dan’s. For Ben to interact with the nearest object, you must press Q, which brings up a verb coin where you need to use the mouse to select an action. If there are two or more objects in your interacting range, you press E to cycle through them before Qing. Finally, if you want to look at something far away, you hold the right mouse button to make a sluggish pointer appear, manoeuvre it over the thing you want to look at, and press Q. It’s a very complicated interface, and one that’s 90% keyboard but you still have to awkwardly reach for the mouse every now and then. Although I did eventually get used to it (and it’s still better than Grim Fandango’s tank controls) I can’t help but wonder why Ben doesn’t just have a standard mouse pointer.

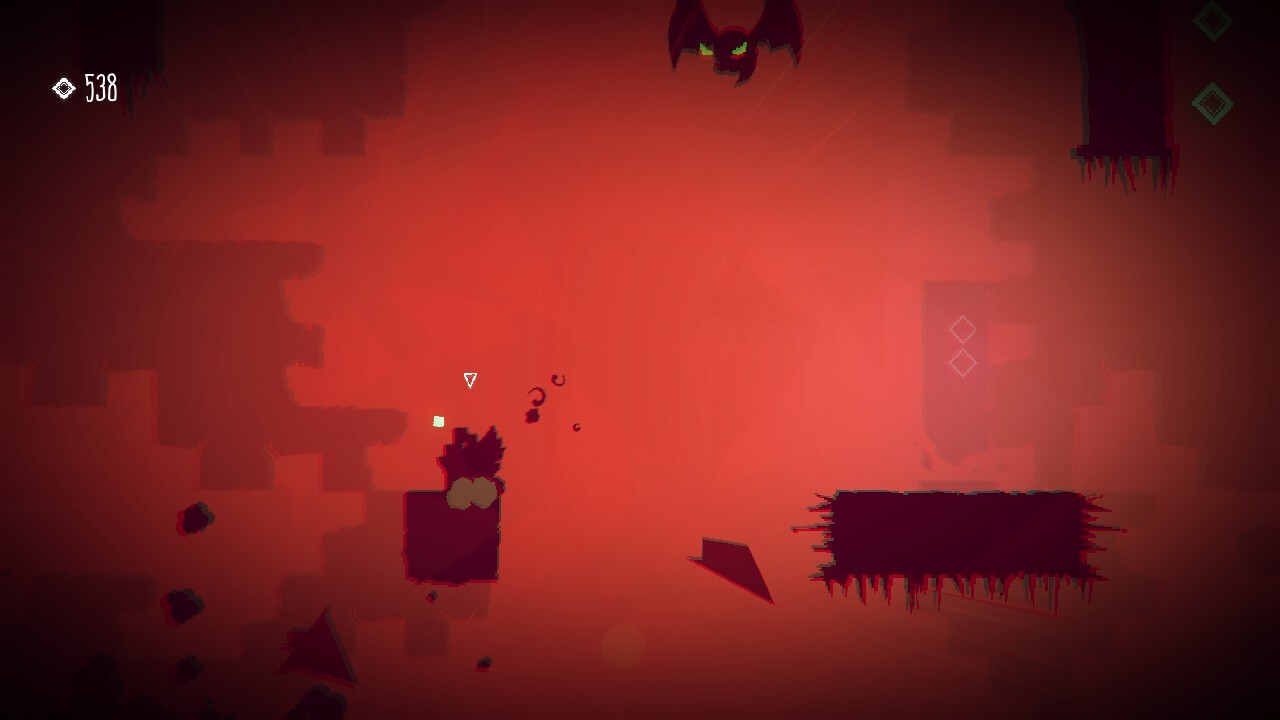

Clockwork God riffs on pretentious indie platformers and adventure conventions in close to equal measure, but its heart is clearly still with the latter genre. Many of the pure platforming segments are exercises in frustration, lacking the atmosphere and engagement of a game that plays this stuff seriously – the price one pays for parody, perhaps. One such segment in the late game explicitly spells out its intention to make you angry. The game is at its best when adventuring with Ben, or when Dan’s platforming is explicitly dependant on Ben’s adventuring. When the two are disconnected, the purely mechanical nature of the platforming quickly grows dreary, as the bulk of the story and humour is delivered through the adventure component.

Seeing red.

Fortunately, among its impressive selection of accessibility settings, Clockwork God provides a “platform assist” slider, which can be used to tweak the difficulty of the platforming sections to reduce (or increase) your frustration levels. Keep in mind that you have to restart the game after changing it.

But these are minor complaints. That a combination adventure/platformer does not reach the highest pinnacle of design in both genres is not a black mark against its name. Whatever deficiencies it has in pure platforming, it makes up for in consistently funny writing, creative settings, and a number of extremely clever puzzle solutions – there’s one that even involves a whole separate game. There’s also a particularly ingenious puzzle solution near the end of the game which I don’t think I’ve ever seen before. After getting it, I stopped playing for a good five minutes just to appreciate its boldness.

Spoilers: don’t click unless you’ve finished the game, you’ll regret it.

Lair of the Clockwork God is well worth your time if you like adventure games, British humour and/or games about games. The platformer aspect adds some variety, but it’s not something that I would recommend on its own, or something that should get in your way if you don’t usually go for it.

The two earlier games are also well worth it, and can be had for a very reasonable fee. It turns out that decade-later sequels can also be good.

David Yates.

David Yates.