Stardew Valley is a 2D RPG/farming simulator (no, not that kind) developed entirely by Eric “ConcernedApe” Barone, and taking inspiration from the peaceful Harvest Moon series of games. It’s a sandbox sort of game about farming, fishing, foraging, foundry-ing,1 fighting and friendship, but could also be described as 16-bit heroin.

I avoided purchasing Stardew for the longest time because of this latter quality. Just looking at the screenshots I could tell it was the sort of game I would lose days, if not weeks to. I eventually did purchase and play it during last year’s December holidays. This is one of the reasons why there were no posts on this blog that month.

# Gameplay

Stardew Valley is a much deeper game than its cheerful and simplistic appearance would seem to belie. There’s a lot to do each day, and a lot of factors to take into consideration in order to make your farm succeed.

Collect all 16 different types of scarecrow!

Farming is of course the main point of the game, and comes with a lot of different variables to consider. Different plants grow in different seasons, have different growth times and produce different yields. Some plants produce multiple yields of multiple produce items, and some only produce one item before needing to be replanted from new seeds. Plants need to be protected from crows and watered daily (either by a watering can you can upgrade or automatic sprinklers), and different types of fertilisers are available to increase the quality of produce and speed of growth, and provide other benefits such as water retention. Once harvested, plants can be sold immediately, processed into preserves or wines, or used to produce meals.

And that’s just crops: farming also includes raising animals: chickens for eggs, cows for milk, sheep and rabbits for wool and pigs for… truffles (clearly everyone in Stardew Valley is a pescetarian). Animal products, like crops, can all be sold as-is or processed into more refined and profitable products: cheese, mayonnaise, truffle oil, etc… Animals must be fed hay, which is harvested from grass grown on the farm, which they can also graze from directly.

Fishing is kind of annoying. It has a similar depth to the other components: you use a fishing rod which can be upgraded and given all sorts of enhancing accoutrements and different types of bait. The fish you catch depend on the season, time of day, and whether you’re fishing in a lake, a river or the ocean. But it’s all centred around a minigame that sorely tried my patience and has been the victim of multiple difficulty-decreasing game mods.

Foraging is fairly basic: as you walk around the game world, you pick up items depending on the season and the favour you have with the RNG gods. Flowers grow in the dirt and berries come off bushes, that sort of thing. There are also occasionally dig spots which you can hoe up to discover other items. And you can also chop down trees for wood – sounds familiar – which brings us to…

Foundry-ing. You go into the mines and dig up stone, coal and ores with your pickaxe.2 You use stone to build things, and you use coal and ores to create bars, which are also used for crafting items and constructing buildings, and for upgrading your tools: watering can, pickaxe, hoe and axe (swords and fishing rods can’t be crafted but must be found or bought).

Fighting is another mine activity. While mining for stone and ores, you’re attacked by monsters you must fight off with your sword (or slingshot, if you can figure out the controls). These monsters drop useful and often valuable items, and can be killed for rewards.

Your healthbar is only shown in dangerous areas.

In addition to selling items for cash and upgrading your tools, you can also craft tools and decorations from them. This is one of the ways the game binds its different elements together: in order to improve your farm, you have to go fishing and foraging to find ingredients to craft into good fertiliser, and mining so that you can craft sprinklers and processing stations. In order to fish better, you have to fight monsters in the mine so that you can craft their remains into bait. In order to fight monsters better, you have to farm ingredients for meals that boost your stats. And so on, in interlocking circles, forever.

# Story

The overarching story of Stardew Valley is that you, an office drone disillusioned with corporate life, are willed a farm by your recently deceased grandfather, and decide to quit your job and go out and make a go of living off the land. Thusly set up, most of the rest of the game story concerns life in Pelican Town, the small village next to your farm.

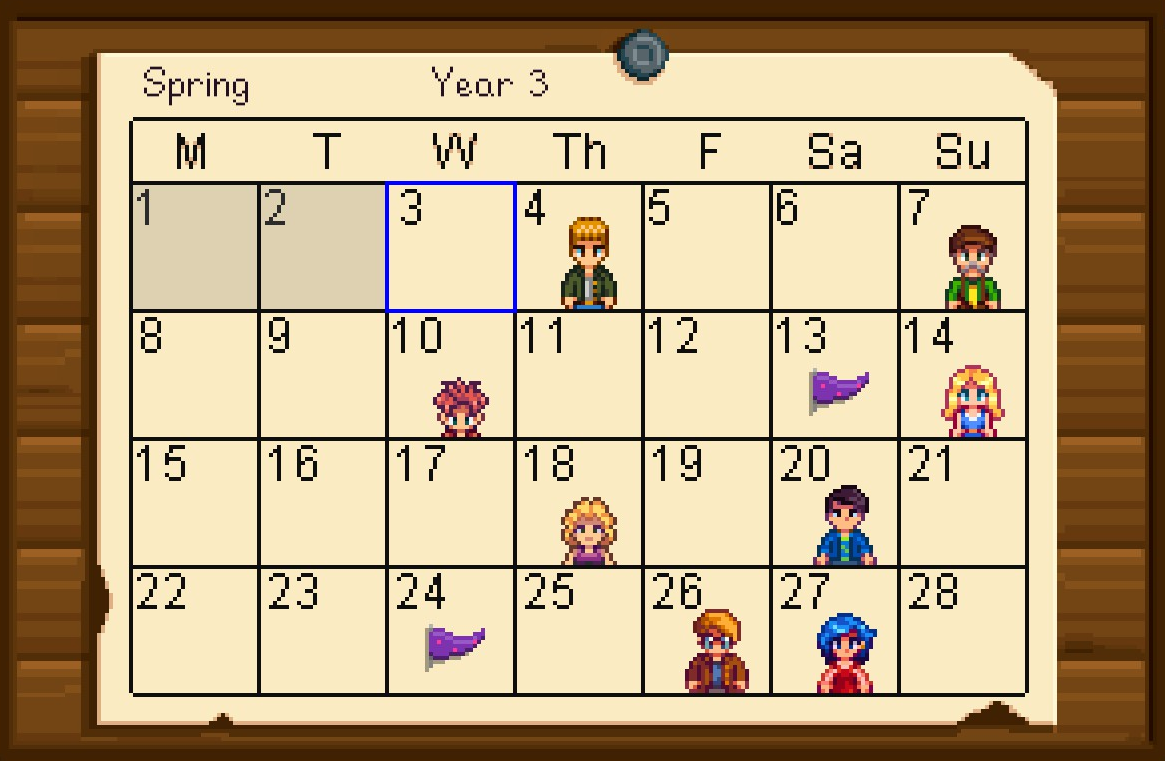

If you’ve been reading carefully, you’ll notice I left the game’s sixth F, Friendship, out of the previous section. Pelican Town and the surrounding areas are inhabited by a large cast of characters, most of whom you can befriend over the course of the game. You do this by giving them gifts to increase their friendship meter: your gifts should be items the character likes or loves, and it really helps if you give them something on their birthday. Characters’ birthdays are easy enough to find out from the in-game calendar, but discovering their favourite items requires either a lot of trial and error or a trip to the official game wiki (another legacy of Minecraft).

Each year consists of four twenty-eight-day months that double as seasons. Spring is first, followed by Summer, Fall and then Winter.

This isn’t a very fun element gameplay-wise, but it’s redeemed somewhat by being a vehicle for story. As the friendship meter goes up for a given character, you’re shown a sequence of small scenes with that character, displaying elements of their personality and their relationships with other characters, oftentimes giving you a deeper and more sympathetic viewpoint of that character. Just about every named character in the game has multiple scenes like this, and it makes the game world feel a bit deeper: slightly more real, slightly less sugar-coated and saccharine.

Around ten of the characters in the game are potential romantic partners for the player character, which in gameplay terms means their friendship meter can go up a bit higher, they have a couple of extra friendship scenes, and you can give them special items to date and eventually marry them. Such marriage is basically an end-game state – the character moves into the farm house, decorates one of the rooms and cycles through a new set of stock phrases. You can choose to have kids as well, but there’s not much to that either. About the most exciting thing you can do after getting married and having kids is to use certain late-game features to get rid of your spouse and kids and start over with someone else.3

The general store, which inexplicably closes on Wednesdays.

The same repetitive cycle you can achieve with marriage and remarriage is reflected in much of the rest of the game. Each season/month has two special events – a Christmas-analogue in Winter, a Halloween-analogue in Fall, a Valentines-analogue in Summer, and so on. While these events are an interesting diversion in the first year, later on they feel dull and samey, with all the townspeople offering the same comments they offered last year, and all the special prizes and purchasable items already know quantities.

In addition to marriage and festivals, the game offers a couple of main quests/story arcs that don’t repeat. Through careful planning and with extensive reference to the wiki4, you can acquire all the items needed to finish the largest of these within a year, but it’s more likely to take at least two, depending on luck. Once that’s completed, there are a couple of other small quests to get access to a couple more areas, and you can obviously keep expanding your farm and buying more things.

Once I got to the end of the second year, I’d finished the main quest, discovered all the locations, fully upgraded my farmhouse and achieved most of everything I’d wanted to achieve in the game. Not coincidentally, the end of the second year is when the player character’s grandfather returns to evaluate their progress and reward them (or not).

Though it’s perfectly possible to keep playing after this point – and plenty of people have continued for many in-game years – getting a positive evaluation felt to me like a very satisfactory end to the game, coming just as I was starting to get bored of it. A clear arc had reached its end, and I quit the game feeling a sense of accomplishment and a warm glow. Despite Stardew Valley’s many Skinner Box qualities, an obvious ending is provided and slightly encouraged, if not forced, allowing it to retain its charm and not descend entirely into mindless repetition.

# Conclusion

Stardew Valley is a bright and colourful feel-good game with surprisingly depth and real heart beneath its slightly-too-sweet aesthetic. Some of its anti-corporate, pro-small-town messages are a little heavy-handed, and it does get old after a while, but that’s just as well, because otherwise I would still be playing it instead of writing this review. If you enjoy resource management, colourful pixel art and a pleasant abstraction of farming, play it now.

In this post-Minecraft era, a game’s not a game unless it somehow incorporates the extraction and smelting of at least four different ores. ↩︎

Just to be clear, I am totally in favour of Stardew Valley’s Minecraft-esque elements. It would be a much poorer game without them. ↩︎

Or the same person, for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind fans. ↩︎

Subject for a future post: player-compiled game wikis. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.