Netflix is developing a new adaptation of CS Lewis’s classic children’s fantasy series, The Chronicles of Narnia. The series has been partially adapted before, into a BBC TV series in the 1980s and a film trilogy by Disney and Walden Media in the 2000s, which covered four and three of the seven books respectively. Little is known about the project, except that they have the rights to all seven books this time, so most articles about it are opinion and speculation. I read one such piece recently which really stuck in my craw.

Netfllix’s Chronicles of Narnia Reboot Using The Original Books’ Ending Would Be A Huge Mistake

This article argues that the final book, The Last Battle, should be changed for the adaptation, essentially for commercial reasons. The core of the author’s argument is made beneath the Orwellian heading “The Chronicles Of Narnia’s Ending Doesn’t Work In 2023”:

The actual ending of The Chronicles of Narnia novels won’t work as the ending to the upcoming Netflix adaptation. In the realms of literature and fantasy, few works have captivated readers as enchantingly as The Chronicles of Narnia. The timeless tales of Narnia have always been steeped in allegory, mainly influenced by Lewis’s Protestant Christian beliefs. The story’s heavy religious undertones, particularly at the end of the final volume, The Last Battle, risk alienating those from other faiths. Even those who share that faith may not wish to see such a heavy-handed portrayal in an escapist fantasy series.

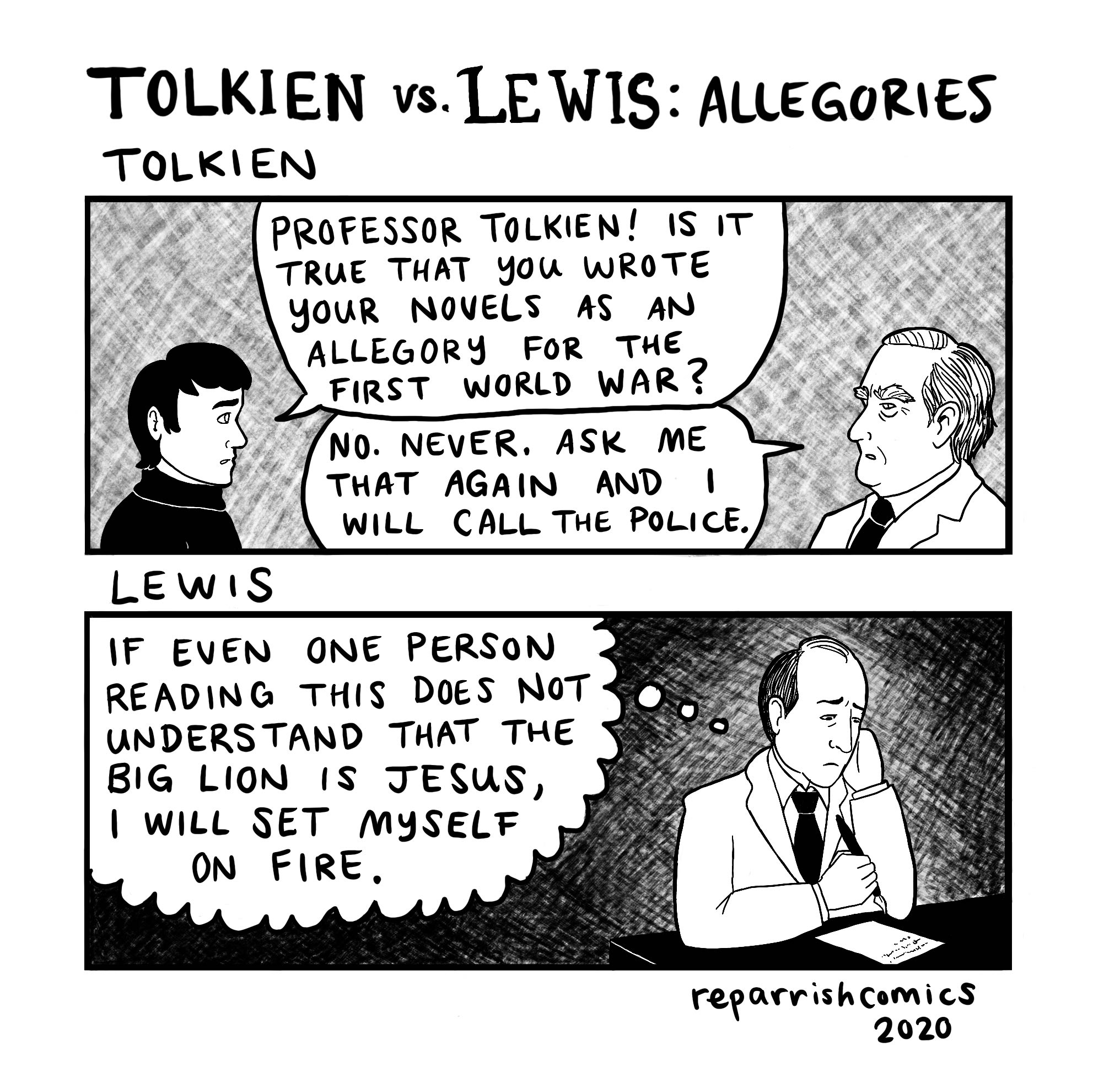

Apart from reading like it was generated by ChatGPT, this text makes me wonder if the writer is even familiar with Narnia. In the first1 and most well-known book, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, we are introduced to Aslan, the Great Lion, who is Narnia’s true king and its divine creator. At about the midpoint of the narrative, Aslan offers himself as a sacrifice in place of the traitor Edmund Pevensie. He is tied to a stone table and put to death by the evil White Witch. The next day, he comes back to life and ends the White Witch’s century-long tyranny over Narnia. Remind you of anything?

Christian themes are pervasive in western literature – at a certain level of abstraction everyone is Jesus in Purgatory. But you don’t have to go hunting for them in Narnia. Who Aslan was supposed to be was obvious to me at the age of six. Lewis was completely unsubtle about this aspect of the work, to the extent that even calling the series a Christian allegory would be too indirect.

If Aslan represented the immaterial Deity in the same way in which Giant Despair [a character in The Pilgrim’s Progress] represents despair, he would be an allegorical figure. In reality, however, he is an invention giving an imaginary answer to the question, ‘What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia, and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?’ This is not allegory at all.

CS Lewis, Letter to Mrs Hook, December 1958

The idea that an adaptation should avoid or tone down the stories’ Christian themes is completely incoherent, whatever your disposition towards those themes, as they’re the very purpose of the work. Picking on just The Last Battle here seems oddly selective; really, the phrase “heavy-handed portrayal” describes Narnia far better than “escapist fantasy series”. Without the Christian elements, you simply don’t have Narnia.

A key difference (and source of disagreement) between Lewis and his friend Tolkien was that the latter strove to create a self-contained world and story that could be appreciated without reference to anything in the real world, and the former did, well, pretty much the opposite of that. So, with Lord of the Rings, any Christian themes are there for you to take or leave as you choose. By contrast, Lewis presents Narnia as a world parallel to our own, which human characters visit and have experiences in that are directly relevant to their lives in our world. He had very specific goals in writing Narnia and made them quite plain to the reader, all but spelling it out:

In your world, I have another name. You must learn to know me by it. That was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.

Aslan, Voyage of the Dawn Treader

Narnia may not be the right property to adapt if you’re uncomfortable with overt Christian themes.

In the next paragraph of the article, we get a few more criticisms of The Last Battle:

Beyond the issue of religion, the ending of The Chronicles of Narnia is bleak and unsatisfying. The sudden demise of all but one of the main cast is disheartening. Moreover, the ending focuses on characters introduced only in the final book, creating a sense of disjointedness from the overarching narrative. If Netflix follows the outline of this original ending, it risks sparking controversy, like Game of Thrones. To avoid falling into the same pitfalls, The Chronicles of Narnia must navigate a delicate balance between preserving its timeless charm and crafting an ending that appeals to the diverse sensibilities of contemporary viewers.

Though this paragraph starts with the words “Beyond the issue of religion”, its contents belie that. Every issue cited in this paragraph comes back to religion. To judge the ending as “bleak and unsatisfying” is a highly materialist view that misses the point entirely, echoing the in-book sentiments of Griffle and his group of dwarves.

And to call it disjointed is to miss the actual overarching narrative, which is that of the world of Narnia, from its creation in the chronologically first book, The Magician’s Nephew, to its destruction in The Last Battle. Just as The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe parallels the death and resurrection of Jesus, these books parallel the creation story in Genesis and the apocalypse in Revelation. Narnia is not supposed to be about the lives of the four Pevensie siblings, and to compare Lewis’s careful artistic choices to the final season of Game of Thrones, which wasn’t even based on a finished book, is facile.

The rest of the article is in much the same vein, permeated by the claim that a faithful adaptation of the Narnia books would be rejected by audiences, who have “diverse sensibilities”, by which the author clearly means “intolerance for Christian children’s books written by a mid-century English professor”. But if that’s true, then why would Netflix even adapt the books in the first place? Surely Lewis’s views can’t be that intolerable to modern audiences if they already like his work and want to see a new adaptation of it.

There’s an underlying push to have a real story with a real message shorn of its identity and turned into a theme park. A desire for Narnia to become a safe, commercialised “universe” populated by bland, interchangeable content that conforms to every current moral fashion and keeps people paying their streaming subscriptions. To cynically use a classic and enduring children’s series as a mere brand. I would greatly prefer a thousand articles about how Narnia represents everything that is most hateful about religion to this mealy-mouthed appeal to commercial blandness.

The Last Battle opens with Shift the Ape bullying Puzzle the Donkey into wearing the skin of a dead lion and impersonating Aslan. Let us hope that Netflix does not intend to do this with the Narnia books. Better, then, that they can the project and adapt Philip Pullman instead. Or maybe they could create something original? Unless, of course, that also Doesn’t Work in 2023.

By publication order, not chronological order. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.