A game I made for a certain kind of person. To hurt them.

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy Steam store description

There’s a scene in Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in which protagonist Rick Deckard uses a VR device to experience the feeling of climbing up a mountain. Through this device, he and thousands of others see and hear what the climber sees and hears and more importantly, feel what the climber feels as he is hit by falling stones. This practice is a core ritual in the book’s fictional religion of Mercerism, meant to encourage empathy.

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy is also about laboriously climbing a mountain in what feels like a painful quasi-religious pilgrimage. The game’s Steam description says it all. I was hurt.

Foddy is responsible for the infamous QWOP and other games in the same vein such as GIRP and CLOP. Getting Over It bears those inspirations, although its control scheme is not quite so bizarre – rather than needing to co-ordinate different leg muscles with carefully planned and timed keystrokes or play Twister with your fingers, you move the mouse to swing a pickaxe in a fairly intuitive manner. The catch is that there are no other controls – you have to move forward and later scale a mountain using just the pickaxe.

The game is intended as an homage to Sexy Hiking, an obscure little Game Maker production released in 2002. As this contemporary-ish review notes, Sexy Hiking is not a slick or polished affair, but its unique pickaxe mechanic makes it an interesting and compelling experience, if not necessarily an all-around pleasant one. It has the same outsider art charm as contemporary Game Maker games like the La La Land and Johnny games.

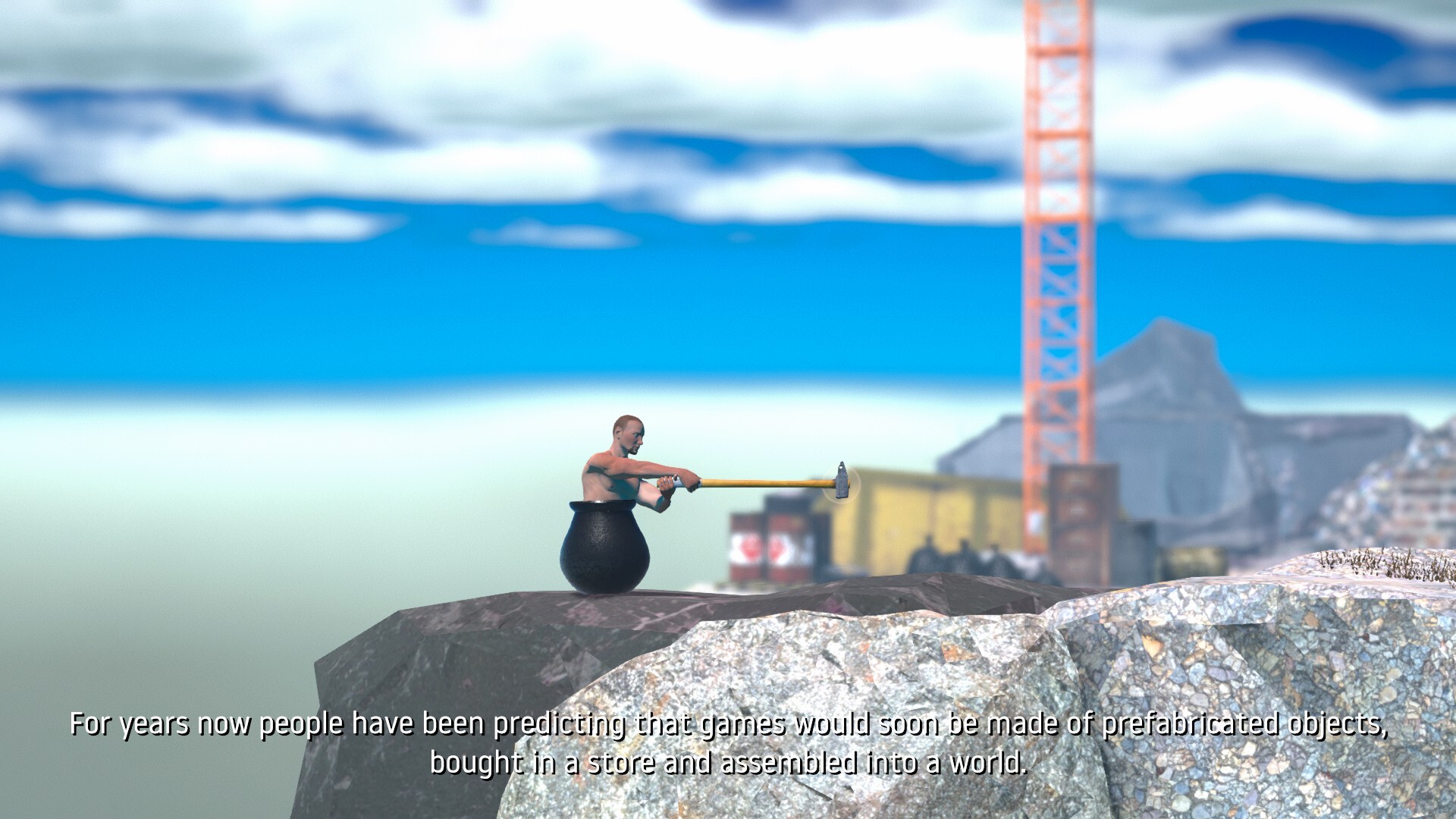

In Getting Over It, Foddy purifies (no arrow-key movement or arbitrary saving and loading here) and expands on Sexy Hiking while keeping the same essential spirit. As you climb higher, the mountain becomes less of a natural rock formation and more of a random pile of mismatching 3D detritus, much of it seemingly taken from some or other indie game asset store.

Those are some familiar barrels.

Weird weird weird. Mixed graphics styles stolen music. Weird EVERYTHING. How did this game keep me interested for a whole hour?

A player comment on Sexy Hiking

What makes Getting Over It more than just an exercise in pure masochism is Foddy’s commentary. At certain points of the climb, he’ll comment on the design of a section, the design of the game as a whole, on failure and frustration, and many other things. Whenever you mistime a swing of your pick and fall all the way back to the bottom of the mountain (this happens a lot), he’ll also pop in with a misattributed quote and a song will play. Hearing more of Foddy’s commentary becomes the reason to climb higher.

At one point, Foddy mentions that while he was building the mountain, he’d invariably make sections of it ludicrously difficult, but then upon playing them feel that rather than having made the game too hard, he just wasn’t a good enough player. On the face of it, this appears to fly against conventional game design wisdom.

Purposeful difficulty is the result of a finely-tuned and well-balanced game mechanic, and thus is “on purpose”. Arbitrary difficulty is the result of bad game design, and thus is arbitrary. Or, to put it another way, purposeful difficulty is the result of the programmer’s competence while arbitrary difficulty is the result of the programmer’s incompetence.

[…]

Anyone can give a boss hundreds of hit points and the player just a handful. Any idiot can flood the screen with enemies and make power-ups/health-ups scarce beyond all reason. All of these things would make a game harder, yes, and they could be the result of a conscious design decision on the part of the creators. But I would still call it arbitrary difficulty because it is difficulty resulting from very bad design decisions, difficulty created for its own sake, just to be frustrating. At a very basic level, this approach misunderstands the entire point of game design and the use of extreme difficulty.

After Pulp Fiction was released, there was a slew of witty, violent crime thrillers that fractured time. But very few of them actually understood the reasons why Tarantino made his film the way he did.

A lot of video game designers are like that: they know that Contra is really hard, and so they make their game really hard, without understanding why Contra is hard. And instead of making the game hard in a fair way, they do it an easy way, by heaping one impossible obstacle after another onto the player in a manifestly arbitrary fashion.

Tom Russell, “Purposeful and Arbitrary Difficulty” in Russell’s Quarterly, issue 1

Still not totally sure what I did to get up there.

The difficulty of Sexy Hiking, the creation of a young and inexperienced developer, was almost certainly more arbitrary than purposeful. Getting Over It consciously emulates that arbitrariness, making no effort to smoothly ramp up its difficulty or reduce player frustration in any way. The whole mountain feels haphazard, like it was constructed without significant consideration of how the player would be able to climb it. Just like a real mountain. Getting Over It is Foddy’s argument against the conventional wisdom of carefully crafted incrementally difficult gameplay and anti-frustration features, in favour of real challenge and struggle.

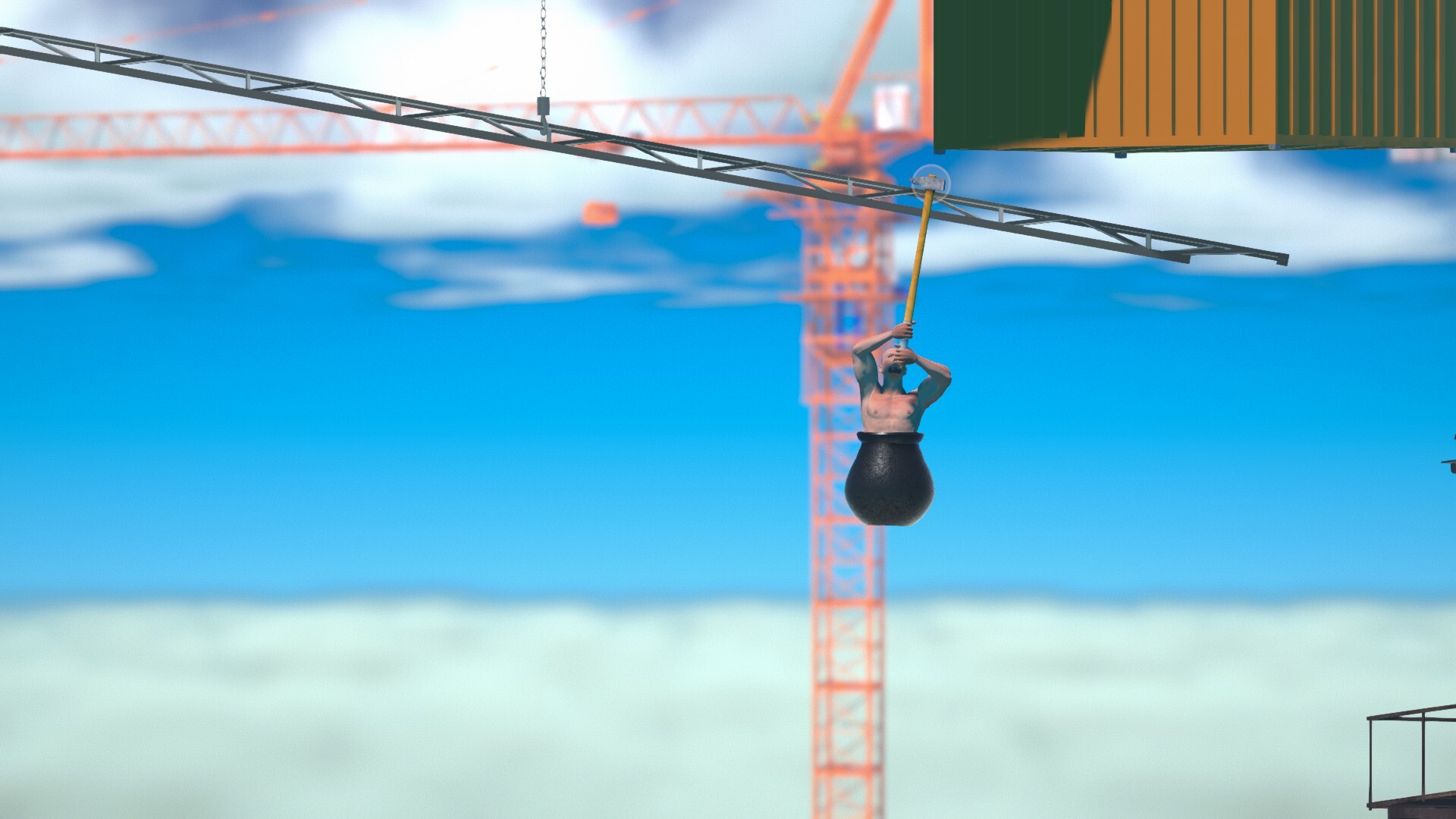

While difficult, Getting Over It is a very fair game. If you accept its central tenants – you can only move with the pickaxe, there’s no way to save scum, and incautious swings will wipe out your progress in seconds – there are no surprises, no apples don’t fall up moments, and at no point do you feel that the game is being unfair. It’s ludicrously difficult, requiring careful thinking, precise timing and a variety of creative uses for your pickaxe, but it is not impossible, and there’s no luck involved.

One of many uses for a pickaxe.

This game is extremely hard, and so the sense of accomplishment from reaching a new point in the climb is real and energising. But for every moment of triumph where your pick catches a jutting ledge just right, there will be at least ten when a careless swing sends you careening back to the start. The highs are high and few, and the lows low and many. If that sounds like your kind of thing, give Getting Over It a swing.

I haven’t finished this game yet and I don’t know when I will. It’s not the sort of thing I can play in long stretches – the pick swinging actually physically hurts my arm after a while, and sometimes I get mad and just have to cool off and come back later – but it’s a uniquely compelling experience and one that I know I’ll find myself coming back to again and again. For now, I’m just going to be proud that I’ve gotten further in this than my 20 metre record in QWOP.

David Yates.

David Yates.