Over a decade ago, I had an Ubuntu install with a broken Unity desktop environment. Rather than fix it, I switched over to a tiling window manager, namely i3. Since then, I’ve used i3 on every new Linux install.

i3 is a window manager for X11, the windowing system used by most *nix systems since the 1980s. A replacement, Wayland, began development in 2008, but is still considered the new kid on the block all these years later. Still, there is a general sense that Wayland is the future, and X11 may eventually stop being actively maintained. Debian, Fedora and Ubuntu have all been defaulting to Wayland for years.

I’ve attempted to switch over to Wayland a couple of times in the past, usually with SwayWM, which advertises itself as a drop-in replacement for i3. My previous experiments with Wayland never offered a compelling reason to stay – my experience would be the same as with X, until something broke or didn’t work as expected. The first time I gave up on Sway and Wayland it was because I couldn’t use my scrollbar to switch between workspaces while hovering my cursor over the workspace buttons on the top bar.1 Incidentally, the creator of i3 has also tried to move to Wayland several times, most recently in January 2026.

In more recent attempts to give Wayland a shot, I branched out from i3/sway and attempted to try Hyprland. It has noted issues with Nvidia hardware, and I’ve never quite been motivated enough to work out how to get past the blank screen it continues to show me even after following various troubleshooting advice.

But most recently, I’ve been seeing some interesting articles about Niri, a tiling window compositor2 with a completely different approach and philosophy to any I’d tried in the past. This was intriguing enough to get me to actually try it, making the leap to Wayland in the process.

# The infinite canvas

As I explained in this post about tiling window managers, the main advantage tiling window managers have over floating window managers is that they arrange your windows for you, making use of all available screen space – snap to side/snap to corner in modern Windows and macOS versions are directly inspired by tiling window managers. Some WMs encourage a more hands-off approach where you define a set of layouts to use automatically, while others require a bit more active management where you have to specify where the next window should appear. Some use the same kinds of workspaces as floating window managers, while others use tag-based workspaces, allowing the same window to appear on multiple workspaces, potentially in different positions.

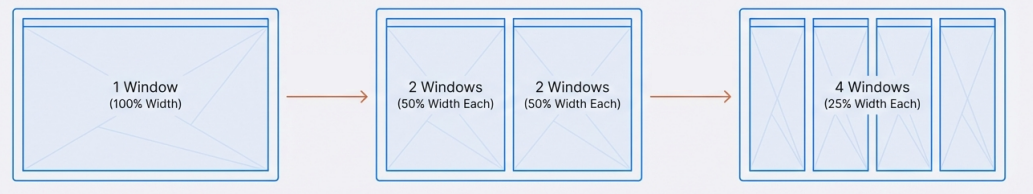

But what all traditional tiling window managers have in common is the space they make available. A workspace is the size of a single screen, and the windows it contains are tiled on that screen. One window will take up the full screen, two windows will take up half the screen each, and so on. i3 has the concept of tabbed or stacked containers, which get you around space constraints to some extent, but sooner or later you’re going to need to switch to a different workspace.

Diagrams courtesy of Google NotebookLM’s slide deck creation feature – with some touchups, because it’s even more keen on unnecessary labels than a parody of a political cartoonist.

If you want to be able to switch workspaces using the number row, you’re limited to ten. After that, you have to start cannibalizing other shortcut keys for named workspaces. If I’m doing a lot of different stuff – different browser profiles, different terminals and Electron apps, etc – or just want to leave things open to come back to them later, I’ll very often run out of numbered workspaces, especially since I need one for each screen.3

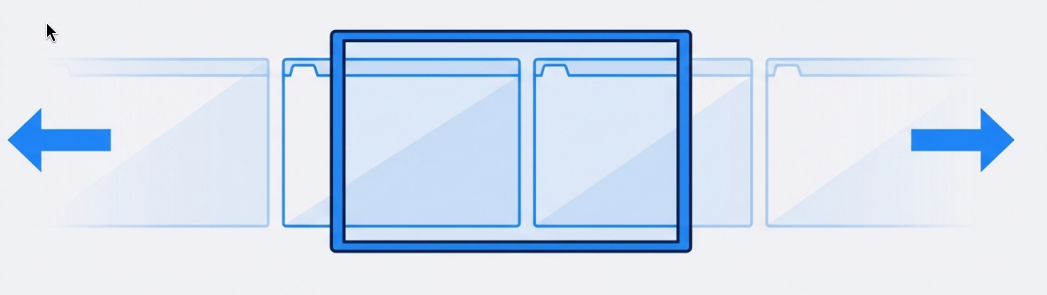

Niri solves this problem in two ways. First, rather than reorganizing the whole screen to squeeze every new window into increasingly limited space, it will always open a new window to the right and scroll to it, pushing the leftmost window(s) off-screen if it has to. The user can navigate back to those left windows using the same controls used to move between visible windows horizontally. This can seem a little strange at first, but is really quite a natural extension of tiling window manager ergonomics. The official demo video shows what this looks like in practice.

Your monitor is a viewport to the infinite workspace.

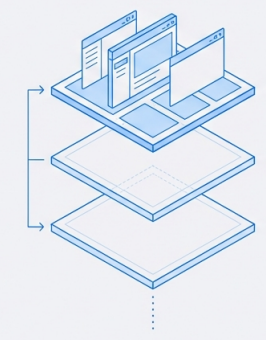

To complement the infinite horizontal scroll within a single workspace, Niri conceptualises multiple workspaces as being vertically stacked. As soon as you place a single window in your current workspace, an empty workspace is created below it. Each output has an independent set of numbered workspaces, starting at 1 and continuing as far as you want. As with i3, you’ll run out of quick jump shortcut keys in the number row after workspace 10, but this doesn’t stop you from creating and using workspace 11, 12, and so on.

An infinite vertical stack

While i3 makes you share your numbered workspaces between displays, Niri gives each display its own set of numbered workspaces. So even if you never go past workspace 10, just having two monitors gives you double the workspaces.

These affordances combine to create a sense of abundance, which is exactly what I should feel running browsers and terminal windows on a modern computer. There is a slight hazard of getting lost, which Niri works to allay through its overview mode, which shows a zoomed out view of your workspaces, and the recently implemented Alt+Tab window switcher, which works exactly how you would expect it to.

As Niri is a scrollable tiling window manager, it still has all the features you’d expect from a tiling window manager – windows can be stacked vertically or put in tab containers just like in i3.

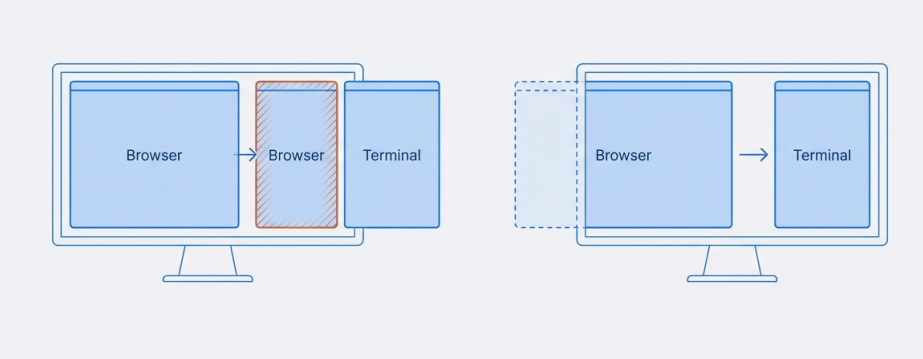

# Don’t go with the reflow

The other key way that Niri differs from traditional tiling window managers is its commitment to preserving the size of existing windows – this is Niri’s foremost design principle. Other tiling window managers will resize whatever they need to in order to fit in a new window, but with Niri you can just open it to the side. This works really well for temporary windows – if I have a fullscreen browser window open, I can open a half-width terminal, have the screen scroll to that, do what I need to do, and then close it again and fall back to my browser.

Who knew tiling could work so well without constantly resizing everything?

Niri is also happy to have a single window open that doesn’t take up the full screen, so you can remember what your desktop wallpaper looks like. On i3, I’d often open a terminal to get my browser to reflow to half-width while reading text on a website that doesn’t restrict line widths. With Niri, I can just resize the browser, and even centre it on screen (Windows-C by default).

# Configuration

Niri is configured through a single KDL text file (~/.config/niri/config.kdl) and autoreloads on config changes. The default config file is comprehensively commented, and a lot of thought has clearly gone into the available commands. For example, while Niri defaults to using movement commands that are confined to the current display and workspace, these can be changed to contextual commands such as focus-column-or-monitor-left and focus-window-or-workspace-down that allow you to move unimpeded through the infinite canvas.

Niri can be configured to be as flashy or as minimal as you like – you can have gaps between windows, rounded corners, transparency, shadows and all sorts of animations, or you can disable all of that for a very utilitarian i3-like setup. I ended up switching to the latter pretty quickly, though I made some tentative and unsuccessful experiments with window gaps and select animations to see if they helped me navigate my windows more effectively.

My one concession to appearance has been to make my status bar and program launcher slightly transparent.

layer-rule {

match namespace="waybar"

match at-startup=true

opacity 0.9

block-out-from "screen-capture"

}

layer-rule {

match namespace="^launcher$"

match at-startup=true

opacity 0.95

block-out-from "screen-capture"

}

This was impossible to achieve with i3 on its own, as i3 is not a compositor – you need an additional program like picom, which I never bothered to set up on X (though Gemini assures me that “almost every” i3 user has). But now that it’s included, I am glad to be able to reach, in 2026, the aesthetic heights of Windows 7’s frosted glass.

# Workspace switcher and status bar

By default, i3 displays the i3bar at the top or bottom of the screen. This bar shows a list of workspaces on the left and some custom status indicators on the right. The configuration for the bar’s general appearance and workspace switcher lives in i3’s config file, but the status indicators must be produced and configured by a separate program – i3status is the default option, but it’s fairly limited. I switched to Conky pretty early on and later to i3blocks, which allows status items to respond to mouse events.

The default alternative to this for a Niri setup on Wayland is Waybar, which is basically i3bar and i3blocks rolled into one. It supports an enormous number of different status indicators and workspace indicators for different Wayland compositors, all of which can be placed on the left, centre or right of the bar; styled with CSS; and be made responsive to mouse events.

After making sure I could use the scrollwheel to navigate through workspaces, I configured the bar to show the current window title in the center and a bunch of indicators on the right – volume, currently playing media, network connectivity, RAM usage, time, etc. I can use the scrollwheel to change the volume or right click to mute it.

I also came up with the idea of using the scrollwheel on the window title to let me cycle through focused windows. This works really nicely, except when the window title is very short.

Waybar has a lot to recommend it, but there are a couple of things that I find annoying:

- Waybar is configured using JSON, and because of the way this JSON is structured, module definitions cannot be shared between outputs. If you want the same stuff on bars across multiple screens, you have to duplicate the relevant module configuration and commit to editing it in more than one place forever.4

- Unlike Niri, Waybar does not autoreload on config changes. You have to either restart it or run

killall -SIGUSR2 waybarto get it to recognize config changes. Sometimes it crashes, either because of config issues or reasons unknown, and then you have to restart it withwaybar & disown.

# Other utilities

Per ArchWiki’s recommendations, I use fuzzel as an application launcher, mako for notifications, swaylock for a lock screen, swayidle to turn monitors off on idle and udiskie to automount USB drives. These are all nice and work well.

I kept Tilix, my favourite terminal from X, because I just don’t like alacritty or kitty all that much. Tilix works fine on Niri unless you try to modify its appearance profile from the right-click menu, whereupon all your terminals instantly crash. As I don’t modify my terminal’s appearance all that often, I can live with this.

For wallpapers, I’m using wpaperd – this allows me to set a different random wallpaper for each of my screens and have them cycle every three hours. It might be cool to really lean into Niri’s scrolling with a scrolling wallpaper like on Android, but I haven’t looked into that yet.

# Pain points

A few things about my setup initially caused me some grief, but were quite easy to fix.

- Hot corner

- By default, Niri shows its overlay mode if you mouse over the top-left corner of the screen, just like Gnome 3. I hate Gnome 3 and all of its “innovations” – it always seemed to me that most of the things it did were just attempts to be different from Windows and MacOS, from putting the program launcher on the left-hand side of the screen to getting people to switch windows with a hot-corner triggered overlay. Fortunately, the corner is easy to disable in

niri/config.kdl.gestures { hot-corners { off } } - Clipboard

- Wayland and the X server run by Xwayland also operate their own clipboards, so native Wayland and Xwayland programs will have different clipboards. Vim in the terminal also uses the X clipboard. Until I realised this, I was pretty confused about why I kept pasting the wrong thing. Installing

wl-clipboard-x11solved the problem by syncing the clipboards.

Some other things are ongoing issues.

- X fallback

- Many programs do not run on Wayland yet, so every compositor worth its salt needs a way to run X applications. This is generally facilitated by Xwayland, which runs an X server and bridges applications to Wayland. For architectural reasons, Xwayland is not something you can just plug into your new Wayland compositor – it requires deep, custom integration. To keep the Niri code clean and avoid having to implement half an X11 window manager inside a Wayland compositor, the author has chosen not to do this integration.

As a lighter alternative, it integrates xwayland-satellite, a generic bridge to Xwayland – a bridge to a bridge. This works until it doesn’t. As of this post, drag and drop does not work between Wayland and Xwayland applications. This is mostly a problem for Krita, the only X-exclusive program I use regularly.5 Steam and various games I’ve tried work fine, even full-screening properly, and I’ve had an okay experience launching my browser and various Electron wrappers in Wayland mode. More crashes than on X, but not deal-breakingly so.

- Screen sharing

- I’ll lead by saying that Wayland lets you do some pretty cool things with screenshots and screen sharing. You can choose programs (chat apps, password managers) and even whole layers (notifications, status bar) to hide from screen shares and/or screenshots. Niri facilitates that through its config and has a bunch of other neat features on top of that. It’s just a bit of a pain to get working,6 and I’ve experienced a lot of freeze-ups in my own use of it. Still experimenting with settings – hopefully this is a surmountable issue.

- Getting lost

- Niri provides both a Windows-style Alt-Tab interface for switching between all windows everywhere and a really slick overview (I like it as long as it’s not triggered by a hot corner), but there’s no default way to see how wide your current workspace is at a glance. I’m considering attempting to get something like papersway’s ‡ indicators working, but for now I’m trying to avoid overusing the infinite horizontal scroll (and underusing the infinite vertical scroll, i.e. workspaces!). Most workspaces should probably be screen-width, with the occasional terminal opened to the right and then closed again.

# Final thoughts

Something I haven’t tried is using Niri with DankMaterialShell, a kind of (very) lightweight desktop environment that provides its own statusbar, launcher, and so on. It looks quite slick, but I’m rather attached to the idea of cobbling my environment out of swappable pieces.

It’s a lot easier to cobble together a personalized environment satisfactorily in the age of LLMs. During my whole Niri setup, I had Claude on-hand to theme things for me, fix bugs, and implement my non-standard configs. A lot of in-the-weeds ricing stuff that I never would have bothered with before is now just a prompt or two away, and most major bugs that first appear to be deal-breakers can be easily overcome.

I have only found out recently that this was definitely a configuration issue. ↩︎

Wayland’s architecture is different enough from X11’s that it has compositors rather than window managers. These architectural differences also seem to be why some compositors work on my Nvidia hardware while others do not. ↩︎

Technically this would be less of a problem with Gnome or Windows-style workspaces that encompass multiple displays, but I find those unacceptably inflexible. ↩︎

Claude recommended using a preprocessor, which would solve this problem, but I can’t get over how insane the idea of using a preprocessor on the config file for my statusbar is. ↩︎

Drag and drop and the occasional crash are the only issues I have with Krita – my old, cheap Wacom tablet works just fine. ↩︎

At least for an ignorant X11 emigrant who has never previously thought about having to configure anything for screen sharing to just work. I learnt all about desktop portals and the abysmal state of my PipeWire configuration. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.