I usually don’t care too much about spoilers, but going into Life is Strange with no idea of what it was about, who the characters were or what the main themes or plot elements were led to some fun surprises. So if you’re in a position to do that, I’d recommend not reading any of this post below the image.

To get it out of the way before we slip into spoiler territory – and I’m talking heavy spoilers – yes, I recommend this game. If you’re at all interested in story-heavy games, if you’ve got narratologist leanings, this is one you’ll want to play. The dialogue doesn’t always sparkle, the gameplay doesn’t always integrate perfectly with the storytelling, and Life is Strange is a really bad name, but it’s all worth it for the good moments, and one ingenious mechanic.

Spoilers begin below the image.

Yes, the protagonist’s surname is Caulfield

Time reversal is the central mechanic of Life is Strange’s gameplay. Similar mechanics were used to great effect in puzzle games like Braid, and Life is Strange has an expected abundance of obstacles to overcome by doing something and then rewinding.1 Where Life is Strange differentiates its time shenanigans is with conversation.

The game’s first couple of puzzles have the same structure. Max, the game’s protagonist, is asked a question in class. Her only response options are variations on “I don’t know”, and regardless of which she chooses, she’s embarrassed and then told the correct answer. She then rewinds time, plays the scenario again, and this time answers correctly. In the next few conversations, she can use this same technique not just to answer questions correctly, but to do-over awkward conversations with clever responses. It’s actionable l’esprit de l’escalier, and on an emotional level, that’s very satisfying. In gameplay terms, it sets up certain expectations: if you just do a conversation over enough times, you can get to an optimal resolution.

This is, of course, unrealistic, and it’s not long before the game brings Max to terms with that. After a few suave conversations and a miraculous rescue, Max runs into the school principle and has to decide whether to tell him that the son of the school’s greatest benefactor was just threatening someone with a gun in the bathroom, or to keep quiet and draw his suspicion. This is presented as the first of the game’s blurry-screened significant and consequential choice between two options.

There’s not really a right answer here.

In a game less invested in its central mechanic, there would exist some contrivance to prevent you from reversing time after a choice like this, but Life is Strange thankfully avoids this. Whichever option you choose, you can easily rewind and choose the other. You can also do this in most other games by save scumming, but here trying and evaluating both options is actually part of the story: Max soon discovers that neither of the two options is optimal and will second-guess her decision and encourage the player to rewind again and again, so you could very well end up flipping between two options three or four times, trying to weigh up and predict their future consequences and generally getting less sure of your choices. Which is very in-character for awkward, uncertain Max Caulfield.2

There is a point where the plot does contrive a way to stop you from reversing time to change the outcome of a pivotal moment, but rather than being a cop-out, it’s in service of the most powerful and effective moment in the game.

One of the earliest characters introduced is Kate. She’s meek, soft-spoken, and on friendly acquaintance terms with Max. In her first appearance, she’s on the receiving end of a thrown ball of paper containing a mean-spirited message. Kate is depressed, and has lately been the target of relentless bullying. It comes to light that this results from an online video taken of her at a wild party while under the influence of drugs she didn’t willingly take.

Over the first two episodes, you make various choices about what Max says to her and whether or not she stands up for her in different situations. Broadly speaking, you choose whether or not to be supportive of her. It all comes to a head when, at the end of the second episode, Max reverses time just as Kate is leaping off the roof of a building. Max has been using her time abilities heavily for hours, to the point of overexertion, and so after reversing Kate’s fall, she has to rush up to the roof and talk Kate out of jumping, all in one go, without rewinds. It’s possible to save her, but also very likely she’ll jump. And because this moment comes before even the halfway point of the season, the game has three more episodes in which to show the consequences, either heartbreaking or uplifting.

While Kate’s story feeds in to the main plot, it’s but one of many subplots in a story that’s mostly focused on a single relationship: the friendship of Max and Chloe, a childhood friend she reconnects with after rescuing from being shot dead by the school bully in a drug-related incident.3

The relationship between Max and Chloe is open to multiple interpretations: both its good and bad points are shown, and the game itself never passes ultimate judgement on whether it’s a healthy friendship, an uneven power relationship, or something else.

In the initial going, I was personally not a big fan of Chloe but later events in the game – most notably a brief foray into an alternate timeline – provide insight into why she is the way she is and who she is underneath her surface-level persona, which made me more sympathetic. Just not quite sympathetic enough to be swayed to her side in the final choice. But more on that later.

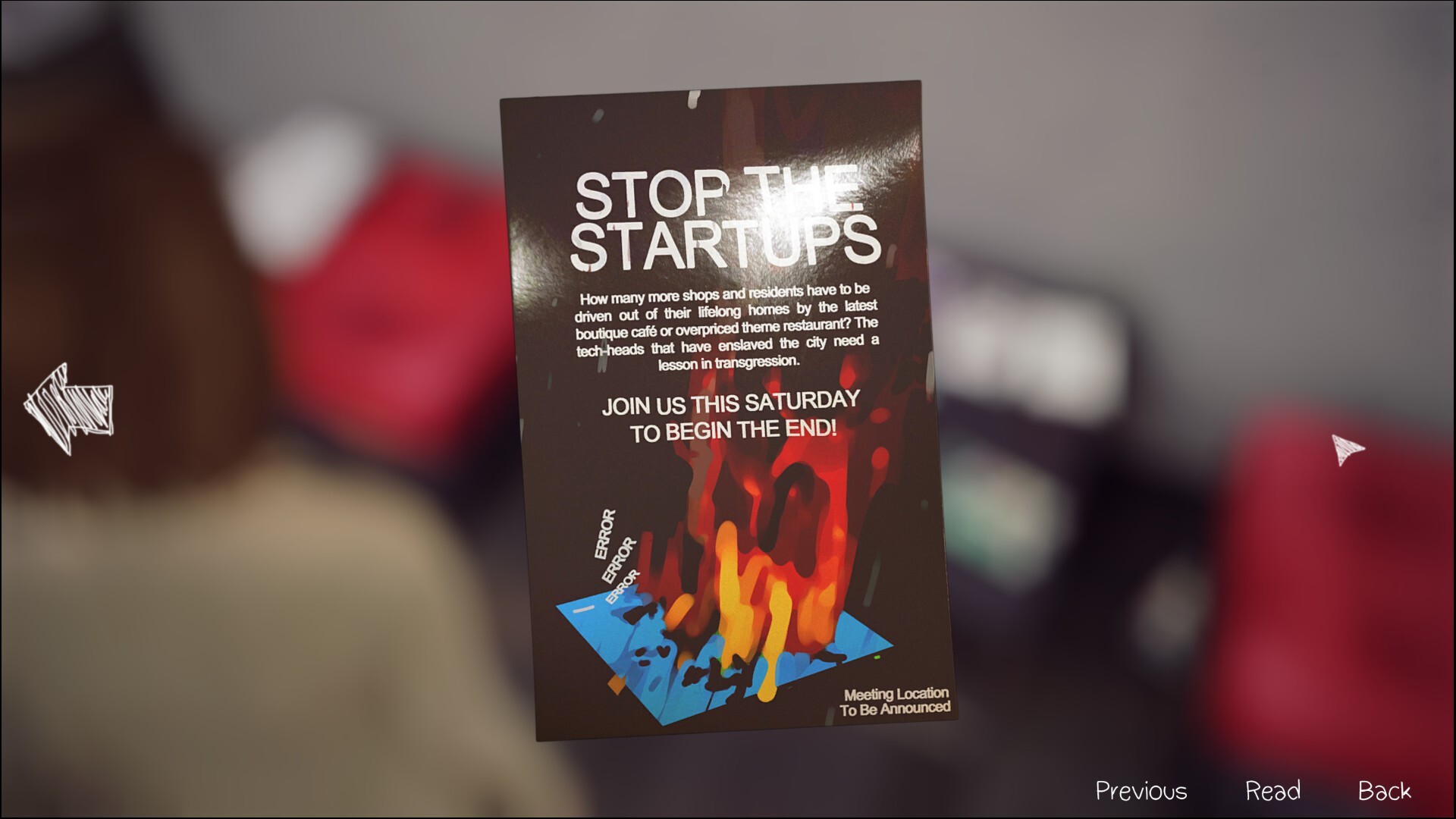

In the last days, San Francisco had an average of two startups per capita.

Graham Nelson once described interactive fiction, the ancestral genre of all story-based games, as “a crossword at war with a narrative.” To some degree, this is true of most other types of games, but nowhere is the conflict as acutely felt as the adventure game and its various children and second cousins. Adventure games strive for complete immersion and the perfect marriage of story and gameplay, so that one cannot be separated from the other, but the worst of them end up little more than low-res movies that destroy their pacing by requiring you to rub random objects together between scenes.

Life is Strange sits somewhere between these two extremes. Much of the gameplay enriches the experience of the story, but at points you find yourself jerked out of the story as it reminds you, “yes, this is an adventure game”.

In normal gameplay, you walk around a given environment talking to characters and looking at or interacting with objects of interest. In public spaces, this feels normal: Max looks at posters and talks to her friends and classmates. But the exact same model of gameplay is used when Max visits the private rooms of other characters, usually with their owners still inside. You are allowed, encouraged, and at many points required to poke through other people’s personal belongings right in front of them. This sociopathic behaviour elicits approximately two reactions over the course of the entire game. “Yes, this is an adventure game,” you say to yourself, as you pull open drawers and search under beds.

That said, I’m not sure what the solution to this gameplay/story tension would be. Story telling and characterisation through player-directed exploration of places is something that games do well, and that you don’t get in any other medium. Life is Strange would be much poorer for leaving out all the descriptions of private possessions, and to its credit the character who should be complaining about your investigation is usually busy with something else in these scenes.

Reminders that you’re playing an adventure game pop up elsewhere. Some of these reminders I found positive, such as the clue board in the fourth episode, which reminded me of my favourite things about the Blackwell series’s notepad, though opinions about both of those things differ. Others, like the overlong bit in the second episode where you have to search for X amount of old bottles, I wasn’t such a big fan of.4

But Life is Strange’s most controversial gameplay element comes at the end. Since Max discovered her time-travel powers, strange and ominous things have been happening with the weather in the game’s setting of Arcadia Bay. It soon becomes apparent that the more Max uses her powers, the worse the weather gets, culminating in a massive hurricane five days after their first use. And seeing as their first use was to save Chloe’s life, Max now has to make a one final choice: go back in time to before she used her powers for the first time and avoid using them at all, thus sacrificing Chloe, or let the town be destroyed by a hurricane.

You know what you have to do.

This final choice has been criticised for erasing the consequences of every preceding choice made since the beginning of the game. Either you prevent every event in the game from happening, or you allow everyone you helped or didn’t help to die in the hurricane.

It’s very clear, by the relative lengths of each of the epilogues, that Dontnod expected players to choose to sacrifice Chloe in order to save the town. This was also the choice I made in the end, with less hesitation than players who had more fondness for Chloe (but still some hesitation – I didn’t hate her!). Moreover, exactly who dies in the ending where you choose to let the hurricane destroy the town is left ambiguous – the official line from the creators is that you should decide who lives and dies for yourself. Frankly, I think that’s a copout and more evidence of which was the intended ending.

One can pose questions about what it means for this kind of interactive storytelling. Can a meaningful and impactful story be constructed out of such malleable pieces? Is it not necessary to have a final choice like this, just to ensure that the proceedings have a suitable conclusion? What does that say about interactive narrative?

That your final choice erases the consequences of every previous choice is something of an occupational hazard for a story about time-travel. Many non-interactive breeds of such stories have similar endings, and so I don’t think it’s any constraint of interactive narrative that compels this final choice. Other games, like the Fallout series, manage to handle this interactivity just fine, ending with detailed, modular epilogues that reflect all of your major and minor choices.

And even in the case of Life is Strange, that the consequences of Max’s actions are ultimately erased is no great sticking point, at least not for me. Aren’t the happenings of all stories (at least those without sequels) erased once you close the book on the last page or finish the credits? Well, no, because you still experienced them, and the same is true in this case. The game’s ending in no way diminishes the many choices and consequences experienced during play.

But yes, a finale that rounded out all of the consequences of choices made during play would have been nice. Maybe we’ll get that in the second season, which Dontnod has confirmed will contain new characters and a new setting, and I can only assume won’t also involve time travel and bad weather.

The late game has you performing a number of clever time tricks, but in the early going, as a bit of characterisation, many of the rewind puzzles involve Max, the main character, fixing her mistakes: there are a number of segments where you’ll reach for something on a top shelf, accidentally drop and break it, and then rewind to do it more carefully. This is acknowledged in about the third episode when Max pulls up a chair to reach something on top of a cupboard the first time around. ↩︎

There’s a lot that can be said about player characters and characterisation thereof. If you have a strongly characterised player character, does showing that in gameplay by preventing out of character actions restrict the player’s freedom? Should you have a strongly characterised PC, a customisable blank slate, or something in between? Criticisms of silent protagonist Gordon Freeman suggest one or two, but not three. ↩︎

If you’re trying to make a story set in highschool exciting for a mostly adult audience, just add drug violence. ↩︎

This seems to have been the majority opinion, and there’s an amusing deprecatory nod to the bottle sequence in the final episode. With any luck, Dontnod have learnt their lesson and won’t be including anything similar in the second season. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.