Daniel Remar’s Iji is one of my favourite games ever. It’s engaging, polished, detailed, complex and very replayable. I first played it shortly after its initial release in about 2008 or 2009, and in total I’ve played it through probably seven or eight times, and I’m not huge on replaying most games (of a highly linear nature, as this one is). I love the way it plays, the levels, the story and the world. I’ve got some of its art on my phone wallpaper rotation, I’ve found most of the secrets, I’ve giggled over the ancillary worldbuilding, but more than that, I’ve had my outlook on serious issues challenged and changed.

As such, I’m not even going to call this a review, because that implies a certain level of objectivity (but not total objectivity) that I am not able to bring to this table. Instead, let’s call this as a discussion of the game, best read by people who have either already played it or have no intention of ever playing it. Much of the article to follow has appeared before in other places, but I’ve done a lot of editing and rearranging for this iteration. If I’m going to be talking more about games on this blog, as I plan to, this article is very necessary context.

Games fascinate me as an expressive medium because of the statements you can make and feelings you can get across that just wouldn’t work in any other form. With a film you sit and watch, with a book you read and imagine, but with a game you actively participate – and active participation can impart whole new levels of meaning. Loneliness is a good, brief example of what I’m talking about – without player participation, it would be a minimalist screensaver.

But because of this participatory element of games, the experience one has with a game is much more subjective and therefore much more personal and likely to vary from individual to individual than with a more passive form of media (not to say those aren’t subjective, because they are, but not to the same degree). What you take away from a game is incredibly dependent on how you play it. You have an influence over your experience that just isn’t present elsewhere. And I will admit that that’s a big part of why I like Iji as much as I do.

I am going to be spoiling the game completely beneath this image. So if that sort of thing bothers you, here’s that link again. You can come back later.

Woo, explosions!

At the beginning of the game, you (Iji Kataiser, the daughter of a research scientist) visit your father’s research laboratory complex with your brother and younger sister. During your visit, strange lights and shapes appear in the sky, and there are a lot of flashes and you ultimately lose consciousness.

You wake up six months later to the sound of scientists discussing how the facility’s been invaded and taken over by aliens, how ‘most everyone is dead and how they’ve reverse engineered the aliens’ nanotechnology and basically made you a cyborg. Then the scientists get murdered. So far, so eye-rolly. I’ll admit I nearly quit the game at this point the first time I played it.

Anyway, you (Iji) are busy dealing with all this when it is revealed that your brother’s still alive, and able to communicate with your over the facility’s intercom system. After the scientists drop, he talks you through your obvious confusion and distress, eventually convincing you to pick up your alien nanogun and use your new alien cyborg abilities to go have a chat with the alien in charge so you can get them all to leave, maybe go invade some other planet.

Gun in hand, you go out into the game. There are aliens out there, and they’re armed and prepared to shoot you on sight, so you take them out before they take you out, as instructed by brother Dan. You (Iji) express some concern about how human they look (humanoid aliens, covered in head-to-toe bodysuits) but your brother says she can’t worry about that. Whatever their appearances, they’re trying to shoot at you, and damnit, they’re evil human-killing invaders who deserve everything they get.

The aliens are called the Tasen, and you find their logbooks scattered around the levels. Logbooks contain everything from hints to secrets to bits of trivia to personal diary entries. You laugh at some of them and identify with others. But they’re still trying to kill you. After you’ve been through a few levels, some of the logbooks talk about you, the “human anomaly” in awed, frightened tones.

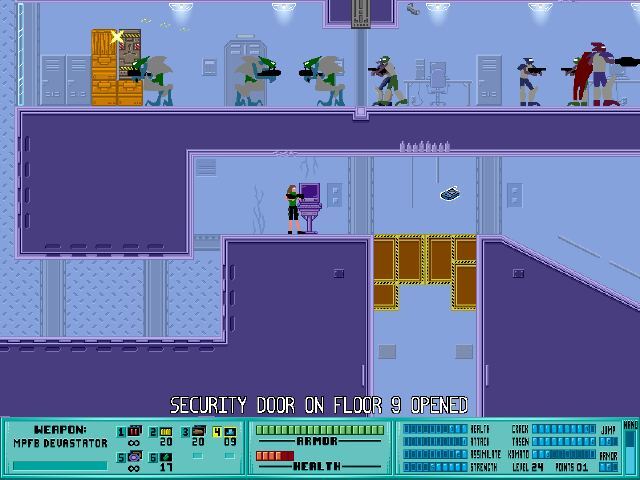

Another, unrelated game. I love me some non-conflicting emotions.

But still: they’re a bunch of human murderers and you’re just shooting in self-defence. This is your planet, they invaded it, and hey, it’s either you or them.

When you get to their boss, he doesn’t want to talk to you. He refuses to listen to anything you have to say and just starts attacking you. Diplomacy is obviously not going to work. So you fight back, and make sure he’s not the one who leaves the room alive.

Following your victory, you discover two new facts:

- The Tasen are hiding from another group of aliens, the Komato, whose ships are just offworld; their scouting team is trapped in the facility and unable to report the presence of Tasen on the planet.

- The entirety of Earth, not just the research facility, has been invaded; most of humanity is probably dead and the planet itself has been ravaged into a wasteland by an Alpha Strike. So the Tasen are a lot worse than you initially imagined.

Your course seems obvious. The Komato are probably some kind of space police, so you get Dan to contact them and inform them of the Tasen presence on the planet. They’ll take out the evil Tasen, and then Earth will be free to rebuild.

When the Komato land, everything goes from bad to worse. Far from being noble space police on the side of humanity against the Tasen invaders, they’re bloodthirsty space Nazis intent on eliminating the Tasen at any cost, and they have no problem shooting at you as well. Turns out the Tasen were just refugees.

So what’s a girl to do? You have to take them out too.

The Komato are the less human-looking ones

The first few times you kill an enemy, Iji apologises. Near the end of the game, when you’ve killed hundreds, she shouts “DIE!” at them. In one of the later levels, your brother Dan is captured by a Komato Assassin, and unless you take a very specific action,1 the Assassin kills him. You exact vengeance on said Assassin by taking his head in the penultimate boss battle – no easy feat, considering how Komato Assassins usually teleport themselves out of a fight if they’re getting too close to death.

Right near the end of the game, you come across the last Tasen outpost, moments after it’s been taken out by the Komato. You hear the screams and explosions as the rag-tag group of aliens are murdered by the army of other aliens. The Tasen on Earth, you’ve found out by now, were the last of their kind in the whole universe. Nice job, Iji, you helped drive a sentient race to extinction.

The final boss battle is against General Tor of the Komato. All your stammered arguments about humanity and defence and Earth have no effect on him. His people want Earth to be completely obliterated (with a higher level Alpha Strike than what was used previously, which would render the planet a burnt husk instead of just a wasteland) to ensure the eradication of the Tasen, and although he tires of bloodshed, he has to bend to the will of the people. The Komato public will not believe the Tasen eradicated until their last-known hiding spot is made into a burnt-out husk. It takes you beating him mostly to death for him to change his mind.

But it works. The planetary annihilation Alpha Strike is called off. The Komato ships leave. Tor dies on Earth. You wander out into the wasteland. Your brother’s dead, most of mankind probably is too, the Tasen are extinct, and you’re the slaughterer of hundreds, Defender of Earth. Cue credits, decorated with pictures of frustrated, sobbing Iji walking around a barren Earth.

At the beginning of the game, I felt justified in killing whoever tried to kill me, and eradicating those responsible for human deaths. At the end, I wasn’t so sure anymore. Was there any other way?

And that’s where Iji really shines: there is another way. It’s a game full of weapons and combat mechanics, and almost everyone you meet in it is trying to kill you, but it’s entirely playable from beginning to end without killing even one person.

Every playthrough I’ve made of the game following the first has been a pacifist run. Instead of killing every alien you see, you realise that you can do just as well by running and dodging them – besides being able to wield nano-weaponery, you also have a pretty resilient nano-shield, after all.

During a run through with this playstyle, you end up making friends with some of the Tasen and even a Komato Assassin. It’s harder to get experience without having it drop off hundreds of corpses, and you have to use some special skills to do some slightly odd things to get past certain fights, but ultimately you can play the game without killing anyone, saving your brother and a few Tasen – to wards the end of the game you can even go into the last Tasen outpost and talk with them – in my original playthrough, I walked through that outpost after everyone inside had just been murdered. The Earth and humanity’s still pretty screwed, but that’s little reason to put more bodies on the pile, and this time the end credits are hopeful.

Iji made me feel guilty about killing off an entire sentient race. It made me completely rethink my stance on self-defence: dishing out violence as you take it in is not the right answer, and moreover, it’s not the only answer, not the only option. The power of the impression it made on me had a lot to do with how I played the game and the kind of mindset I had before playing the game2 but I don’t think I could have got a message like that, with that same sense of personal relevance, from anything other than a game. I wasn’t watching a movie about a girl killing aliens. I was personally pulling the trigger every single time.

Iji had a profound effect on the way I play games and the way I think about the world. I don’t think it had that effect on everybody, and it’s not a perfect game by any stretch of the imagination, and if I hadn’t played it exactly as I did, I probably wouldn’t have liked it as much. To some degree, I feel that I had the game’s intended experience, but I can’t be totally sure of that. And I certainly would have come away from it with a very different impression if I’d gone the pacifist route in the beginning, or if I hadn’t replayed the game.

But I played it like I did, with play-throughs progressing in the above order, and even arguably bad elements of its design reinforced the experience. That’s exciting, and it’s one of the big things that’s exciting about games, to me.

I don’t think it’s something most people can figure out intuitively on first play-through, which perhaps speaks of bad game design, but it was a very effective part of my first play-through experience. ↩︎

I read a review somewhere that complained about its trite, heavy-handedness, and maybe it is to the reviewer, but it wasn’t to me. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.