I

One of my go-to airplane books has for over a year been a collection of Howard Phillips Lovecraft’s best stories, as decided by some or other editor.1 I recently finished the stories in this book and then, interested to find out more about the author, took a look at a biography – A Dreamer and a Visionary: HP Lovecraft in His Time by ST Joshi (a more interesting book overall). My opinion on the man and his writings wavered throughout.

Big elephant-in-the-room issue first: Lovecraft, although a man of rigid scientific principle apt and ready to adapt his every belief (almost) on the receipt of new information, was very racist throughout his life and applied none of this thinking to matters of the inferiority/superiority of certain races compared to others. Even by the standards of his day, he had a very strong racist streak (the TVTropes page on him spends most of its considerable length in hand-wringing over this). This comes through in a number of his stories, such as “The Shadow Over Innesmouth”, which functions in part as an anti-race-mixing parable.

But HPL did have ideas and things to say apart from his unfortunate convictions about racial hierarchy, and it’s these that his fiction (at least in part) is worth reading for. His stories are disinterested in humanity and individual personalities and relationships, and choose to focus instead on setting (HPL was very interested in the American colonial period, especially the British settlements and architecture) and the horror of the unknown and unknowable and vastly different (not always in the racist sense of “foreigners look funny to me”), and of human insignificance in the vast expanse of the universe.

Lovecraft took to heart the conception that, if aliens exist, they are certain to be incomprehensible to us and possessing of entirely alien value systems and motivations – his most interesting stories present these beings and sometimes their societies, and display the great pains he went to make them truly alien.

In my opinion, having now read a reasonable amount of HPL’s later period fiction2, his three vital works are “The Colour Out of Space”, “At the Mountains of Madness” and “The Shadow Out of Time” – these are the stories that showcase HPL at his most essential and with his ideas most fully developed. I think a prospective reader could quite happily read these and consider themselves Lovecrafted-out. “The Call of Cthulhu”, “The Rats in the Walls”, “The Shadow Over Innesmouth” and “The Dunwich Horror” represent a second tier, with the latter three being among his most accessible works and “Cthulhu” needing no introduction.

I say “Lovecrafted-out” in the previous paragraph because despite my respect for HPL’s many admirable qualities – devotion to knowledge, unwavering artistic integrity, and others – and my genuine interest in his strange ideas and rigorously alien aliens, I found it an absolute struggle to get through his pseudo-Victorian prose. It is overblown, adjective-laden, and generally undercuts any sense of horror with a tendency toward the melodramatic – the lack of scariness in all I read led to my conviction that HPL, at his best, was a science-fiction author, and indeed it’s the sci-fi aspirations of “At the Mountains of Madness” and “The Shadow Out of Time” that I appreciate about them.

And that got me thinking about a theory that I’ll get to in a few paragraphs, after I’m done with what’s going to seem like an odd digression, so please bear with me for the next section. It’ll all make sense soon, I promise!

II

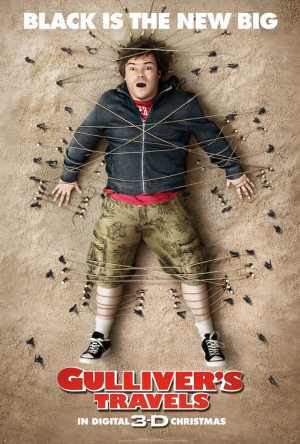

I had totally forgotten about this film until I started Googling around for this article. I imagine you had too.

Some contemporary readers of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels may have picked it up thinking it just another travelogue of some explorer’s trip around the world, and may indeed have held that belief up until the appearance of the tiny inhabitants of Lilliput. It is notable to say that this appearance follows a detailed and credible biography of the man Gulliver and a reasonable account of the start of his voyage. Similarly, Mary Shelley prefaced the story-proper of Frankenstein with a series of letters that frame the entire novel as a story related second-hand to a sea-captain’s sister, providing some solid, real-world explanation for the existence of the story as a printed book. Bram Stoker’s Dracula is presented as a collection of diary entries and letters, and spends a considerable amount of its length explaining how and when the characters update their various diaries.

These fantasy/horror stories were likely told in this manner in order to heighten the reader’s suspension of disbelief, in much the same way horror films like The Blair Witch Project were marketed as found footage – some explanation of how the stories arrived with their tellers makes it easier to believe that the horrors depicted therein are actually real and should therefore make the work more scary.

Another modern example of this is the phenomenon of creepypasta – the collective name given to Internet ghost stories spread around with deliberate ambiguity as to their status as fictional stories, and often taking epistolary formats. That a story is scarier if you don’t have immediate evidence of its fictional nature seems a time-tested bit of conventional wisdom, but I’m not sure it’s as important enough of a factor to merit the lengths writers often go to ensure it.

In the latest episode (at the time of this posting) of his “Scared Yet” creepypasta review series, Kris Straub reviews his own “Candle Cove”. He repeatedly mentions his hope that said story – presented as an excerpt from an online forum thread – would be able to stand on its own as an obvious work of fiction and be scary on those terms rather than need readers to think it a real series of posts in order to feel frightened by it. Personally, I think it absolutely does stand on its own, and I’m very happy for Straub to get his dues as the writer of the piece (something that becomes a little difficult if you’re too committed to the idea of your work as stuff that really happened). More generally, I enjoy and often frightened by good works of creepypasta, but I’m not about to check my closet for Slenderman.

So, to tie this back in with HPL (no, I haven’t forgotten): Most of Lovecraft’s own stories are framed as retrospective first-person narrations, their narrators replete with much-expressed but slowly diminishing skepticism regarding the fantastic events to which they bear witness. In his writings about weird fiction theory3 he speaks a lot about the importance of narrative restraint and realism. This quote pretty well sums it all up:

Inconceivable events and conditions have a special handicap to overcome, and this can be accomplished only through the maintenance of a careful realism in every phase of the story except that touching on the one given marvel.

My issue is that the main source of tedium I find in his stories comes from his painstaking efforts to effect this “careful realism”. It’s very dull to read all of this guff about how skeptical and scientific the viewpoint character is just so that we can be extra horrified by the eldritch abomination he finds under his bed.

III

But as I look at my own biases and tastes, I start to feel like this problem is far more to do with me and my life in the 21st century than to do with HPL’s early 20th century writing. There are two main factors to this:

- The fantastic is in fashion. The biggest movies around are about superheroes, spaceships and epic fantasy lands and have been for more than a decade. We have the special effects to make all of this look incredibly convincing, so you hardly need much suspension of disbelief to think “yes, that man is flying around in a robot suit”.

- Everything is debunkable. You can take a look at the director and cast of a videotape someone found in the woods with a quick Google search, and there’s a whole popular, often-cited website dedicated to debunking urban legends. Mythbusters performs a similar function with a higher budget.

I believe that these two factors have greatly increased the general population’s (or at the very least my personal) ability to suspend disbelief. The modern man would not be in the position of picking up Gulliver’s Travels and thinking it’s a real travelogue, because the Earth is a known place, and because a quick Google search would tell you it’s fiction. And the modern man would not even have to be convinced of its reality to read it, because he’s been trained by movies about superheroes and giant monsters to suspend disbelief and just enjoy the story.

And that’s why I find Lovecraft largely ponderous and irritating to read, and rather miscategorised as a horror writer. I’m ready to believe in weird monsters for the sake of the story, or at least ready enough to not need excessive amounts of convincing that the narrator is of sound and scientific mind. This renders much of the work as tedious filler, especially to someone reading one story after another where it’s obvious something weird’s going to happen but the narrator spends so much time in verbose disbelief and/or trying to chip away at the reader’s presumed disbelief – a presumed disbelief that, once again, isn’t really that impervious. I’m sure it made his stories more excitingly believable at the time – a rare book collector even asked Lovecraft where he could find a copy of the Necronomicon – but it’s not my cup of tea.

Still, the interesting ideas within and occasional sections where his invariable wide-eyed purple prose is appropriate for what’s depicted are worth the slog, at least once. Here’s a handy list:

Essential Tier

- “At the Mountains of Madness”

- “The Colour Out of Space”

- “The Shadow Out of Time”

Solid Tier

- “The Call of Cthulhu”

- “The Shadow Over Innesmouth”

- “The Dunwich Horror”

- “The Rats in the Walls”

Meh Tier

- “The Haunter of the Dark”

- “The Shunned House”

Eh Tier

- “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward”

- “The Whisperer in Darkness”

Awful Tier

- “Herbert West – Reanimator”

I’ll add more if I read more, which could happen.

Boo!

-

Containing “Herbert West – Reanimator”, “The Rats in the Walls”, “The Call of Cthulhu”, “The Dunwich Horror”, “The Whisperer in the Darkness”, “At the Mountains of Madness”, “The Shadow over Innesmouth”, “The Shadow Out of Time”, “The Haunter of the Dark”, “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward”, and notably omitting “The Colour Out of Space” (which, had I been the editor, I would have included in place of the campy and ridiculous “Herbert West”, which really has no place in a collection entitled “The Best of HP Lovecraft”). ↩︎

-

Roughly 1926–1936, the last decade of HPL’s tragically short life, and the time he wrote his most known, praised and not-owing-quite-so-much-to-Poe-or-Dunsany stories. Note that I’m counting only works written by Lovecraft on his own with the intention to publish under his own name in this grouping.4 ↩︎

-

“Weird fiction” as a genre doesn’t appear to have seen much use since the 1930s, so forgive me for referring to HPL’s genre as “horror” in some places this piece – personally I consider his best work science fiction and his worst rather ineffective melodramatic horror. I’d much sooner drop Robert Aickman’s work in the genre, though he insisted on “strange stories”. ↩︎

-

An interesting consequence of HPL’s becoming massively more known in death than he was in life is that people have seen fit to republish works he ghost-wrote for others (his main source of income) under his own name. It’s useful for completionists and scholars, but we can only guess at what he’d feel about it. I have not read many of these works and do not personally consider them part of his work proper. ↩︎

David Yates.

David Yates.